by Natalie Zend

This essay pays homage to some of my primary influences and inspirations as a facilitator. I wrote it in honour of the work of the Transformative Learning/Spirit Matters Community, for inclusion in its book Transformative Learning in the 21st Century: Revisioning Education around the Planet, intended for publication by Zed Books, London, UK, in 2015. Illness within the editorial team has held up publication of the book, but I share the essay here as an expression of what motivates my work with groups and organizations.

Summary

The Transformative Learning Centre (TLC) gatherings have shown me that people can come together in ways more co-creative, more whole, more emergent, and more expansive than what my time in academia and government would have given me to believe was possible. These times are calling for wide participation: the kind of authentic inquiry, collective meaning-making, and co-creativity that only a flattening of hierarchy can allow. When power is distributed and emergent, every moment of speech and of listening can become an act of leadership. In this spirit, each TLC gathering has the flavour of a stone soup: each participant adds their ingredient into a single pot until a delicious and nourishing meal materializes, seemingly out of nothing. Unlike in the traditional conference, there is nothing canned about it.

This global crossroads is also asking for deep participation. The assumption that we are separate and can dominate and use other people and the planet for the benefit of a few has led us to a precarious brink of time. To break free from it, we need to reconnect with the knowing that resides not just in the mind, but deep in the body, the heart, and the spirit. TLC events, though academic, invite not just our cognitive, but also our embodied knowing—whether through acoustic improvisation, circle dancing, shamanic ceremony and invocation, participatory art-making, theatre performance, journaling, open mic nights and dance parties, or graphic recording. This kind of multi-modal embrace of our broadest humanity is vital for us to bring about a just, thriving, sustainable world.

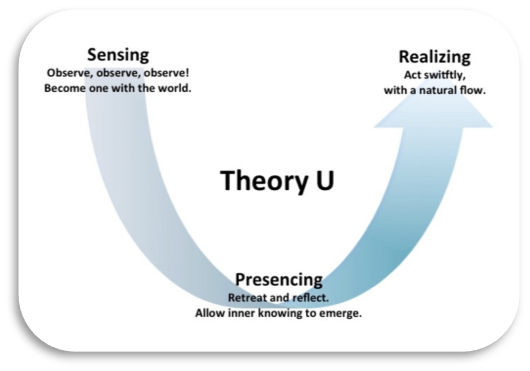

The TLC conferences have shown me the creative power and importance of carefully held containers for genuine dialogue. They become gateways for emergence and evolutionary portals into higher levels of humanity. Since my first encounter with TLC in 2007, holding these kinds of spaces has turned into a calling. I’ve become a host, facilitator and trainer. I’ve studied and worked with numerous frameworks and tools for holding conversations that matter, from Open Space Technology, the Work that Reconnects and Theory U, to circle process, Participatory Learning and Action, Deep Democracy, and Questions for Inner Guidance. I’ve deepened my sound and movement improvisation practice so that I can regularly feel the future come through my own body-heart-mind-spirit—and help others do the same. Ultimately, all of my work now is about helping people listen together for possibility – and feel more wholly alive while doing it.

This global crossroads is also asking for deep participation. The assumption that we are separate and can dominate and use other people and the planet for the benefit of a few has led us to a precarious brink of time. To break free from it, we need to reconnect with the knowing that resides not just in the mind, but deep in the body, the heart, and the spirit. TLC events, though academic, invite not just our cognitive, but also our embodied knowing—whether through acoustic improvisation, circle dancing, shamanic ceremony and invocation, participatory art-making, theatre performance, journaling, open mic nights and dance parties, or graphic recording. This kind of multi-modal embrace of our broadest humanity is vital for us to bring about a just, thriving, sustainable world.

The TLC conferences have shown me the creative power and importance of carefully held containers for genuine dialogue. They become gateways for emergence and evolutionary portals into higher levels of humanity. Since my first encounter with TLC in 2007, holding these kinds of spaces has turned into a calling. I’ve become a host, facilitator and trainer. I’ve studied and worked with numerous frameworks and tools for holding conversations that matter, from Open Space Technology, the Work that Reconnects and Theory U, to circle process, Participatory Learning and Action, Deep Democracy, and Questions for Inner Guidance. I’ve deepened my sound and movement improvisation practice so that I can regularly feel the future come through my own body-heart-mind-spirit—and help others do the same. Ultimately, all of my work now is about helping people listen together for possibility – and feel more wholly alive while doing it.

Dialogue—The Final Frontier: Stone Soup for the Soul

I first encountered the Transformative Learning Centre (TLC) when I attended the “One Earth Community” Spirit Matters Conference in April of 2007. It seems a miracle that I attended at all, for that weekend I was slated to be in Ottawa for the third of four retreats in an extended Nonviolent Communication leadership program. For me to pull out of such a commitment was quite out of character, but somehow I had a strong feeling that I had to be at Spirit Matters. What I felt was: I need to see how it can be done. What? A different kind of conference. I sensed that this event, by virtue of its process and structure—not even to mention its content—would redefine my understanding of what a gathering of people could be, and that somehow the experience would change my life. And it did.

In me were inchoate yearnings for gatherings more widely and deeply participatory, that is, more co-creative, more whole, more emergent, and more expansive than what my time in academia and government would have given me to believe was possible. And that is what I experienced at One Earth Community, and even more deeply at each subsequent TLC event. At the time I surely couldn’t fully have named my longings, but something in me heard the call. These years later the call has turned into a calling.

In me were inchoate yearnings for gatherings more widely and deeply participatory, that is, more co-creative, more whole, more emergent, and more expansive than what my time in academia and government would have given me to believe was possible. And that is what I experienced at One Earth Community, and even more deeply at each subsequent TLC event. At the time I surely couldn’t fully have named my longings, but something in me heard the call. These years later the call has turned into a calling.

Collective Intelligence—An Essential Response in Uncharted Territory

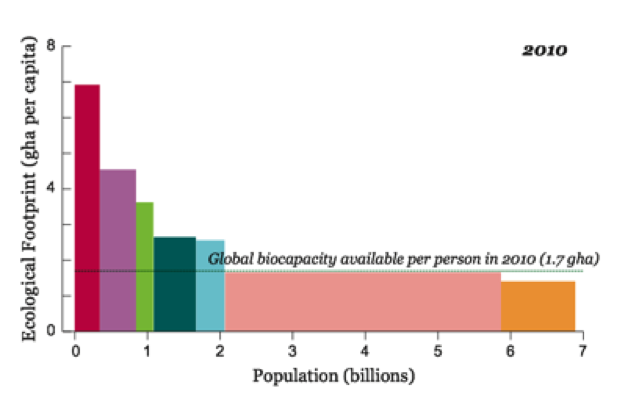

Click heLet me explain. We are in an unprecedented planet-time. Humanity has never before faced such uncertainty about the continuity of complex life on Earth. The nuclear age, climate change, and mass species extinction, not to mention peak oil and global economic crisis, have in a geological instant brought us to levels of complexity for which our hundreds of millennia of existence on this earth have not prepared us. We are in uncharted territory. We simply have never been here before, and the ways of being, thinking and doing that have brought us to this brink may not keep us afloat in these choppy waters. These times are asking us to do millennia of evolving in a few short years. Luckily, as futurist Barbara Marx Hubbard points out, “quantum transformations are in nature’s tradition,” and “crisis precedes transformation.” (1998:103)

As Einstein famously said, “a new type of thinking is essential if mankind is to survive and move toward higher levels.”[i] (1946) And I would add that it is not merely an up-leveling of our consciousness as individuals that is needed. Our collective survival requires collective intelligence. Together we can--at our best—vehicle more wisdom than any one of us can alone. This is an age that asks for, not one strong visionary leader or ideology to steer our course, but a continual accessing of wisdom that is more than the sum of us. It requires a kind of collective learning that “dramatically and irreversibly alters our way of being in the world.” (O’Sullivan, 2002) Tom Atlee calls this co-intelligence, “the ability to wisely organize our lives together…in tune with each other and nature.” If we are to embrace and transform the challenges of this time, we need to access the fullness of our collective potential.

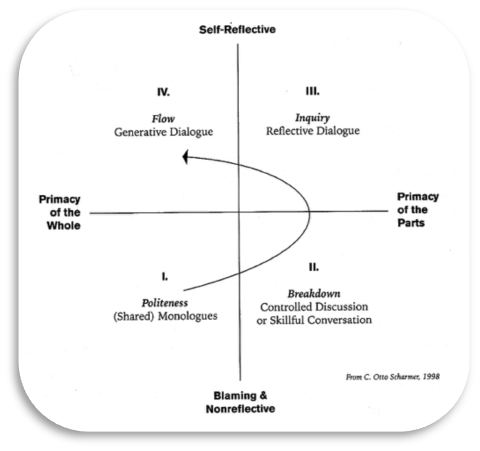

Yet our current mainstream institutions and systems for organizing our lives together often end up producing less than the sum of the parts. Our collective conversations are frequently exercises in competition and compromise that result in win-lose outcomes. Seen from a wider lens, win-lose is in truth lose-lose. As Otto Scharmer of MIT writes, “we collectively create outcomes (and side effects) that nobody wants.” (2007: 7) And we seldom get beyond what he typologizes as the first two (of four) fields of conversation, which he calls “blaming and non-reflective.” (in Isaacs, 1999)

As Einstein famously said, “a new type of thinking is essential if mankind is to survive and move toward higher levels.”[i] (1946) And I would add that it is not merely an up-leveling of our consciousness as individuals that is needed. Our collective survival requires collective intelligence. Together we can--at our best—vehicle more wisdom than any one of us can alone. This is an age that asks for, not one strong visionary leader or ideology to steer our course, but a continual accessing of wisdom that is more than the sum of us. It requires a kind of collective learning that “dramatically and irreversibly alters our way of being in the world.” (O’Sullivan, 2002) Tom Atlee calls this co-intelligence, “the ability to wisely organize our lives together…in tune with each other and nature.” If we are to embrace and transform the challenges of this time, we need to access the fullness of our collective potential.

Yet our current mainstream institutions and systems for organizing our lives together often end up producing less than the sum of the parts. Our collective conversations are frequently exercises in competition and compromise that result in win-lose outcomes. Seen from a wider lens, win-lose is in truth lose-lose. As Otto Scharmer of MIT writes, “we collectively create outcomes (and side effects) that nobody wants.” (2007: 7) And we seldom get beyond what he typologizes as the first two (of four) fields of conversation, which he calls “blaming and non-reflective.” (in Isaacs, 1999)

Fig. 1 Scharmer’s Four Fields of Conversation (Isaacs, 1999). CC License by the Presencing Institute – Otto Scharmer

In the first field, “politeness,” or “shared monologues,” individuals download one after the other what they already know. This aptly describes much of what I have witnessed during the scores of academic, government and civil society conferences I attended during my graduate studies and later in my decade of work with the Canadian government’s international aid agency. Thinkers and doers come together to present research findings one after the other, or to make policy pronouncements or recommendations. In the best cases, the findings are revelatory and the recommendations are inspiring and grounded calls to action. But the conversation is in some essential way stale. The coffee breaks are the moments of greatest creativity and innovation. These are the kinds of gatherings that prompted Harrison Owen (2008) to invent Open Space Technology—a way of holding a meeting that is all coffee break.

If there is enough safety in the container for people to open their minds and express and respond to opposing views, a gathering might enter the second field that Scharmer (in Isaacs, 1999) calls “breakdown,” or in later writings (2007), “debate.” Here, divergent views compete with each other to determine the collective course of action. This is the prevalent mode of interaction in our parliaments and courtrooms. These two fields of conversation are important and even necessary, but when we loop between these two we stop short of the full potential of the collective that is so needed in this time.

Fortunately, as Scharmer has so helpfully charted, there is a territory beyond conversation as usual—what William Isaacs calls “dialogue” or “the art of thinking together.” (1999) Isaacs (in Burkhardt, 2010) calls this “a new frontier for human beings – perhaps the true final frontier.” “In it,” he says, “we come to know ourselves and our relatedness to the whole of Life.” This is the kind of conversation that leaves its participants expanded, deepened, and lifted into higher possibility. People surprise themselves when they express what they’ve never heard or thought before, as if their words are being drawn forth by the moment itself.

When someone slows down and begins to reflect on his or her positions, a conversation might enter the third field, which Scharmer (in Isaacs, 1999) calls “inquiry” or “reflective dialogue.” Here, people suspend their habitual judgements, assumptions and concepts. No longer fully identified with who they think they are and what they think they know, they are able to stand in another’s shoes and open their hearts to another’s experience. Room for multiple perspectives opens up and genuine inquiry becomes possible. New ways of seeing and doing begin to emerge.

The fourth field is the most rare. Sharmer (in Isaacs, 1999) calls it “flow,” or “generative dialogue.” It comes about when there is reflection on the process as a whole, intention toward the highest end the group or conversation might serve, and attention to the future that is wanting to emerge. As Kate Sutherland articulates it, here there is a “sense of oneness, as though whoever speaks voices the collective intelligence of the group.” (2012: 72) This is truly the realm of thinking together, of co-creating. As Tom Atlee so poetically puts it, in this space individuals access “the wisdom of the whole on behalf of the whole.” (n.d.) This is where the group gains direct access to what David Bohm called the “implicate order,” the unmanifest field of infinite potential. (1996)

And this is where I come back to Spirit Matters. I intuited that this event would show me possibilities of conversation more alive, more transformative, more co-creative, than what I’d previously experienced in any traditional conference. I didn’t have the maps for this territory then, but in my depths I knew we were crossing that final frontier into reflective and generative dialogue, and that we—and the world—would be changed for the better.

If there is enough safety in the container for people to open their minds and express and respond to opposing views, a gathering might enter the second field that Scharmer (in Isaacs, 1999) calls “breakdown,” or in later writings (2007), “debate.” Here, divergent views compete with each other to determine the collective course of action. This is the prevalent mode of interaction in our parliaments and courtrooms. These two fields of conversation are important and even necessary, but when we loop between these two we stop short of the full potential of the collective that is so needed in this time.

Fortunately, as Scharmer has so helpfully charted, there is a territory beyond conversation as usual—what William Isaacs calls “dialogue” or “the art of thinking together.” (1999) Isaacs (in Burkhardt, 2010) calls this “a new frontier for human beings – perhaps the true final frontier.” “In it,” he says, “we come to know ourselves and our relatedness to the whole of Life.” This is the kind of conversation that leaves its participants expanded, deepened, and lifted into higher possibility. People surprise themselves when they express what they’ve never heard or thought before, as if their words are being drawn forth by the moment itself.

When someone slows down and begins to reflect on his or her positions, a conversation might enter the third field, which Scharmer (in Isaacs, 1999) calls “inquiry” or “reflective dialogue.” Here, people suspend their habitual judgements, assumptions and concepts. No longer fully identified with who they think they are and what they think they know, they are able to stand in another’s shoes and open their hearts to another’s experience. Room for multiple perspectives opens up and genuine inquiry becomes possible. New ways of seeing and doing begin to emerge.

The fourth field is the most rare. Sharmer (in Isaacs, 1999) calls it “flow,” or “generative dialogue.” It comes about when there is reflection on the process as a whole, intention toward the highest end the group or conversation might serve, and attention to the future that is wanting to emerge. As Kate Sutherland articulates it, here there is a “sense of oneness, as though whoever speaks voices the collective intelligence of the group.” (2012: 72) This is truly the realm of thinking together, of co-creating. As Tom Atlee so poetically puts it, in this space individuals access “the wisdom of the whole on behalf of the whole.” (n.d.) This is where the group gains direct access to what David Bohm called the “implicate order,” the unmanifest field of infinite potential. (1996)

And this is where I come back to Spirit Matters. I intuited that this event would show me possibilities of conversation more alive, more transformative, more co-creative, than what I’d previously experienced in any traditional conference. I didn’t have the maps for this territory then, but in my depths I knew we were crossing that final frontier into reflective and generative dialogue, and that we—and the world—would be changed for the better.

Wide Participation: Tapping the Experts, Sharing the Leadership

One series of moments exemplifies the alchemical fields of dialogue we entered during that and subsequent TLC events. These dialogues didn’t even involve words, yet they gave participants an embodied experience of collective generativity that rippled out into our spoken exchanges. At the outset of plenary sessions, physician, therapist and musician Larry Nusbaum would offer up his treasure chest of “weapons of mass percussion” to the participants, inviting each of the several hundred gathered to choose an instrument if they wished. He would then invite us to remember a place in nature we loved and notice the sounds there. He would tell us:

In nature, there are no wrong notes. All sounds and no sounds are welcome. All rhythms and no rhythm are welcome. If it’s good enough for nature, for the next few minutes, let it be good enough for us. You can’t blow it! In a few moments, I will invite us to sit in silence and listen deeply. At some point, someone will feel the impulse to make a sound. We have no idea who it will be. The sound may come from an instrument, or a voice, and we will listen. Then someone else will feel the call to make a sound, and we will listen. The sounds will come in slowly, or not so slowly. They may be harmonic, or chaotic, or may move between the two, and we will listen. The sound will carry us for about eight to ten minutes and find its own way to end. We have no idea how it will end, but the sound will bring us back to silence. We will then sit in this new silence for a time and marinate in the transformation that has occurred.

And that is exactly what would happen: out of the pregnant silence, would emerge a magical tapestry of sound, whole and harmonious even in moments of dissonance or syncopation. With no score, no composer, no conductor, and no metronome, music would issue out of stillness. Tone and notes, rhythm and pace, would find their way into the sonic space. And then, just as magically as it had emerged from the silence, somehow the soundscape would settle into a new silence. Each participant, at once performer and audience, would become creator and witness of something beautiful never before manifest in the visible (audible) realm. This collective improvisational music-making became a living metaphor as well as a “critical yeast” (Lederach, 2005) for the co-creativity that emerged in our plenary councils and dialogue circles.

What enabled us to break through into the realm of authentic inquiry and co-creativity was, first and foremost, a flattening of hierarchy. In the music-making, as in our dialogue circles, there was no specified leader or even facilitator, but rather an “animator.” Just as Larry created a sense of freedom for everybody to follow inner impulses and promptings, the animators’ role was to “hold the safety of the space for a diversity of opinions and viewpoints to be expressed in an atmosphere of mutual interest and respect.” (TLC, 2007a) This allowed the leadership to be distributed and emergent. Every act of speech and of listening could become an act of leadership.

The very architecture of our dialogues, the circle, sent quite a different message from the traditional arrangement of podium and chairs in rows. We are not here to passively receive someone’s expertise, it instantly conveyed: everyone here is a leader. As someone in the gathering said, “experts are on tap, not on top.”[i] Indeed, the “Councils” that preceded each dialogue circle consisted of “a conversation among four or more featured animators in front of a full assembly of participants, […] a coming together of wisdom leaders from a diversity of peoples, ways of knowing and experience.” (TLC, 2007b) The Councils were intended to “water and seed the dialogue circles with in-depth discussion themes and questions,” rather than, as in a traditional conference, to be forums for invited experts and leaders to impart their knowledge in a one-way flow.

The music-making, the dialogues, and indeed each TLC gathering as a whole, thus has the flavour of a stone soup: each participant adds their ingredient into a single pot until a delicious and nourishing meal materializes, seemingly out of nothing. Unlike in the traditional conference, there is nothing canned about it. In this way, participation in collective meaning-making is wide, inviting and involving the voice of each of the people in attendance.

What enabled us to break through into the realm of authentic inquiry and co-creativity was, first and foremost, a flattening of hierarchy. In the music-making, as in our dialogue circles, there was no specified leader or even facilitator, but rather an “animator.” Just as Larry created a sense of freedom for everybody to follow inner impulses and promptings, the animators’ role was to “hold the safety of the space for a diversity of opinions and viewpoints to be expressed in an atmosphere of mutual interest and respect.” (TLC, 2007a) This allowed the leadership to be distributed and emergent. Every act of speech and of listening could become an act of leadership.

The very architecture of our dialogues, the circle, sent quite a different message from the traditional arrangement of podium and chairs in rows. We are not here to passively receive someone’s expertise, it instantly conveyed: everyone here is a leader. As someone in the gathering said, “experts are on tap, not on top.”[i] Indeed, the “Councils” that preceded each dialogue circle consisted of “a conversation among four or more featured animators in front of a full assembly of participants, […] a coming together of wisdom leaders from a diversity of peoples, ways of knowing and experience.” (TLC, 2007b) The Councils were intended to “water and seed the dialogue circles with in-depth discussion themes and questions,” rather than, as in a traditional conference, to be forums for invited experts and leaders to impart their knowledge in a one-way flow.

The music-making, the dialogues, and indeed each TLC gathering as a whole, thus has the flavour of a stone soup: each participant adds their ingredient into a single pot until a delicious and nourishing meal materializes, seemingly out of nothing. Unlike in the traditional conference, there is nothing canned about it. In this way, participation in collective meaning-making is wide, inviting and involving the voice of each of the people in attendance.

Deep Participation: Coming in Whole, Knowing what we Know

Participation was not only wide, it was also deep, and this was another vital condition that brought us into a field of collective intelligence. We were invited to participate not, as eco-philosopher Joanna Macy is fond of saying, merely as “brains on a stick,” but as whole human beings: body-heart-mind-spirits (1998). In traditional conferences as in mainstream society, the cerebral is given primacy of place, along with the verbal and the visual. And in this privileging of mind over body, reason over emotion, knowledge over intuition, visible over invisible, masculine over feminine, heaven over earth, we lose access to so much wisdom and guidance. In fact, we lose our way. Cut off from the deeper knowing that resides in the body, the heart, and the spirit, it is easier to remain caught up in the mistaken assumption that we are separate and can dominate and use other people and the planet for the benefit of a few.

But in this gathering, as in the subsequent TLC events, we were invited to bring the whole of ourselves. There was not just the acoustic improvising, but also circle dancing, shamanic ceremony and invocation, participatory art-making, theatre performance, journaling, open mic nights and dance parties, and graphic recording. All these elements modeled a broader tapping into all that is available to us, and thus called forth a fuller sweep of our human capacity. They invited not just our cognitive, but our embodied knowing.

In a global conjuncture we’ve never before faced, this kind of multi-modal embrace of our broadest humanity comes to be much more than a fun triviality. It is a necessity, if we are to emerge from the chrysalis into a thriving, sustainable human presence on this planet. As cosmologist Brian Swimme notes (cited in Hart), without a cultural precedent to face the ecological loss before us, we are not even able to fathom many of the facts of our current predicament. (2005: 8) Ecologist and evolutionary biologist Guy McPherson points out that the human brain is unable to compute the implications for climate change—and human survival—of exponential growth and amplifying feedback loops. (2013) Yet, in eco-psychologist Rebekah Hart’s words, “the intelligent body has within it the ability to adapt to new situations. […] Only the body can feel the complex implications of our reality.” She cites philosopher and therapist Eugene Gendlin (1992): “The body senses the whole situation, and it urges, it implicitly shapes our next action.” (2005: 8)

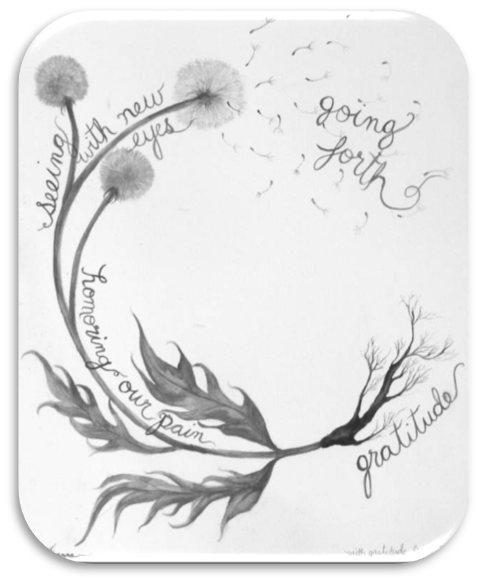

It is not just the body that knows, but our hearts too are vital to our survival and our ability to nurture the continuity of life. As Joanna Macy writes, when we deny or repress the pain in our hearts—the grief, fear, anger, and sadness that naturally occur in the face of the unprecedented threats to life on Earth, “our power to take part in the healing of our world is diminished.” “Our experience of pain for the world,” she says, “springs from our inter-connectedness with all beings, from which also arises our powers to act on their behalf.” It is not enough to have a cognitive understanding of the crises we face, we need to actually experience our painful feelings. “Only then,” writes Macy, “can they reveal on a visceral level our mutual belonging to the web of life.” (n.d.a)

The 2007 gathering explicitly wove into the fabric of its schedule both time and space for “willingly enduring our pain” for the earth (Macy, n.d.b), in effect taking us through a natural process of transformation that Macy calls “the spiral of the Work that Reconnects.” The second council and the dialogue circles that followed centred on “facing our challenges: what disrupts, fragments and keeps us numb from the realities of our interconnection in One Earth Community, e.g. […] war, ecological devastation, abuses and injustice, […] all of which must be confronted creatively.” (TLC, 2007a) As in life, “honouring our pain,” (in Macy’s words) naturally brought us to into “seeing with new eyes” and “going forth” in an empowered and enlivened way. In the next council, “From Grief into Vision,” our pain, as evidence of our interconnectedness, was what steered us toward “bigger, more complex and participatory worldviews within a framework of emancipatory and grounded hope.” (TLC, 2007a)

But in this gathering, as in the subsequent TLC events, we were invited to bring the whole of ourselves. There was not just the acoustic improvising, but also circle dancing, shamanic ceremony and invocation, participatory art-making, theatre performance, journaling, open mic nights and dance parties, and graphic recording. All these elements modeled a broader tapping into all that is available to us, and thus called forth a fuller sweep of our human capacity. They invited not just our cognitive, but our embodied knowing.

In a global conjuncture we’ve never before faced, this kind of multi-modal embrace of our broadest humanity comes to be much more than a fun triviality. It is a necessity, if we are to emerge from the chrysalis into a thriving, sustainable human presence on this planet. As cosmologist Brian Swimme notes (cited in Hart), without a cultural precedent to face the ecological loss before us, we are not even able to fathom many of the facts of our current predicament. (2005: 8) Ecologist and evolutionary biologist Guy McPherson points out that the human brain is unable to compute the implications for climate change—and human survival—of exponential growth and amplifying feedback loops. (2013) Yet, in eco-psychologist Rebekah Hart’s words, “the intelligent body has within it the ability to adapt to new situations. […] Only the body can feel the complex implications of our reality.” She cites philosopher and therapist Eugene Gendlin (1992): “The body senses the whole situation, and it urges, it implicitly shapes our next action.” (2005: 8)

It is not just the body that knows, but our hearts too are vital to our survival and our ability to nurture the continuity of life. As Joanna Macy writes, when we deny or repress the pain in our hearts—the grief, fear, anger, and sadness that naturally occur in the face of the unprecedented threats to life on Earth, “our power to take part in the healing of our world is diminished.” “Our experience of pain for the world,” she says, “springs from our inter-connectedness with all beings, from which also arises our powers to act on their behalf.” It is not enough to have a cognitive understanding of the crises we face, we need to actually experience our painful feelings. “Only then,” writes Macy, “can they reveal on a visceral level our mutual belonging to the web of life.” (n.d.a)

The 2007 gathering explicitly wove into the fabric of its schedule both time and space for “willingly enduring our pain” for the earth (Macy, n.d.b), in effect taking us through a natural process of transformation that Macy calls “the spiral of the Work that Reconnects.” The second council and the dialogue circles that followed centred on “facing our challenges: what disrupts, fragments and keeps us numb from the realities of our interconnection in One Earth Community, e.g. […] war, ecological devastation, abuses and injustice, […] all of which must be confronted creatively.” (TLC, 2007a) As in life, “honouring our pain,” (in Macy’s words) naturally brought us to into “seeing with new eyes” and “going forth” in an empowered and enlivened way. In the next council, “From Grief into Vision,” our pain, as evidence of our interconnectedness, was what steered us toward “bigger, more complex and participatory worldviews within a framework of emancipatory and grounded hope.” (TLC, 2007a)

Even beyond the deep knowing of body and heart, the Spirit Matters events, as the very name indicates, have opened space for the wisdom and guidance of spirit. In the dominant Western paradigm, only what the five senses can apprehend is real—and in living from that assumption we block out vast fields of knowing. To touch the full extent of what is available to us, we need collective spaces where access to the invisible is socially acceptable. The TLC has created just that—gatherings where, as one 2007 participant said, people are safe to “come out of the closet as spiritual beings.” In safe containers such as this, like radio antennae or wifi routers we can open to realms unseen and channel the riches that lie therein. Within what Jung called the personal and collective unconscious—territory of ancestors, future beings, archetypes—lie crucial keys to navigating the uncharted waters of these times.

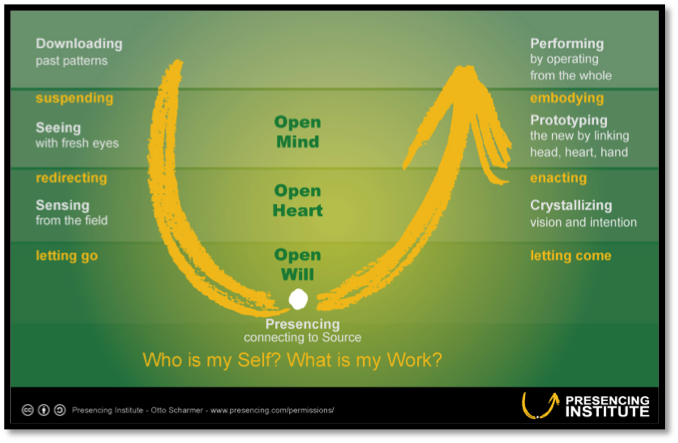

At bottom, deep participation is a movement of progressive opening and ever-deeper listening. As we open our minds, our hearts and our wills, we tap into what Joseph Jaworski calls “the creative Source of infinite potential enfolded in the universe.” Connected to this Source, we become vessels for creation, “partners in the unfolding of the universe.” (2012: viii) As Scharmer describes in his ground-breaking work, Theory U, rather than only “learning from the experiences of the past,” we begin to “learn from the future as it emerges.” We “sense, tune in, and act from [our] highest future potential—the future that depends on us to bring it into being.” (2012: 7)

At bottom, deep participation is a movement of progressive opening and ever-deeper listening. As we open our minds, our hearts and our wills, we tap into what Joseph Jaworski calls “the creative Source of infinite potential enfolded in the universe.” Connected to this Source, we become vessels for creation, “partners in the unfolding of the universe.” (2012: viii) As Scharmer describes in his ground-breaking work, Theory U, rather than only “learning from the experiences of the past,” we begin to “learn from the future as it emerges.” We “sense, tune in, and act from [our] highest future potential—the future that depends on us to bring it into being.” (2012: 7)

At the 2007 gathering, Six Nations elder Diane Longboat remarked, “I stopped going to conferences because they always had an agenda. Because they were not guided by spirit they never reached their outcomes.”[i] If despite this, she has come to the TLC events, I imagine it is because unlike traditional conferences, they have not stifled creativity and innovation with rigid mind-made agendas and pre-determined goals. On the contrary, they have offered carefully held containers that have become gateways for emergence, portals into the “higher levels” of humanity Einstein presaged. Scharmer’s description of the shift of a social field aptly conveys what the TLC is offering the world in this time of unparalleled metamorphosis:

What I see rising [from the rubble of our modern age] is a new form of presence and power that starts to grow […] from and through small groups and networks of people. It’s a different quality of connection, a different way of being present with one another and with what wants to emerge. When groups begin to operate from a real future possibility, they start to tap into a different social field from the one they normally experience. It manifests through a shift in the quality of thinking, conversing, and collective action. When that shift happens, people can connect with a deeper source of creativity and knowing and move beyond the patterns of the past. (2007: 4)

Since that fateful TLC gathering in 2007, helping this shift to happen has become my calling. I’ve become a host, facilitator, trainer and improvisation enthusiast. I’ve studied and worked with numerous frameworks and tools for hosting conversations that matter, from Open Space Technology, the Work that Reconnects and Theory U, to circle process, Participatory Learning and Action, Deep Democracy, and Questions for Inner Guidance. I’ve deepened my sound and movement improvisation practice so that I can regularly feel the future come through my own body-heart-mind-spirit—and help others do the same. Ultimately, all of my work now is about helping people listen together for possibility – and feel more wholly alive while doing it. Just as the TLC has been doing since its inception. Because there’s a new world emerging, and we are the ones who get to create it.

References

Atlee, Tom. (n.d.) Home page of The Co-Intelligence Institute. Retrieved July 20, 2014, from http://www.co-intelligence.org.

Bohm, David (1996). On Dialogue. London and New York: Routledge Classics.

Burkhardt, Vern (2010). Thinking Together, Part 1, IdeaConnection Interview with William Isaacs, Author of Dialogue: The Art of Thinking Together. Retrieved July 20, 2014 from http://www.ideaconnection.com/open-innovation-articles/00172-Thinking-Together-Part-1.html.

Einstein, Albert (1946, May 25). Atomic Education Urged by Einstein. The New York Times.

Gendlin, Eugene T (1992). The Primacy of the Body, Not the Primacy of Perception: How the Body Knows the Situation and Philosophy. Man and World 25.3-4, 341-353.

Hart, Rebekah (2005). Earth Knows, Body Knows: Explorations in the Felt Ecology of an Animate World. Unpublished paper for the McGill School of Environment.

Hubbard, Barbara Marx (1998). Conscious Evolution: Awakening the Power of our Social Potential. San Francisco: New World Library.

Isaacs, William (1999) Dialogue and the Art of Thinking Together. New York: Crown Business.

Jaworski, Joseph (2012). Source: The Inner Path of Knowledge Creation. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Lederach, John Paul (2005). The Moral Imagination: The Art and Soul of Building Peace. Oxford, MA: Oxford University Press.

Macy, Joanna and Young Brown, M (1998). Coming Back to Life: Practices to Reconnect Our Lives, Our World. Gabriola Island, B.C.: New Society Publishers.

Macy, Joanna (n.d.a). Theoretical Foundations, Joanna Macy and Her Work website. Retrieved July 23 2014 from www.joannamacy.net/theworkthatreconnects/theoretical-foundations.html.

Macy, Joanna (n.d.b) Drawing by Dori Midnight, in The Spiral of the Work That Reconnects, Joanna Macy and Her Work website. Retrieved July 23 2014 from http://www.joannamacy.net/theworkthatreconnects/the-wtr-spiral.html. Reproduced with permission.

McPherson, Guy (2013, January 6). Climate-Change Summary and Update. Retrieved July 22 2014 from http://guymcpherson.com/2013/01/climate-change-summary-and-update/.

Owen, Harrison (2008). Open Space Technology: A User’s Guide, 3rd Edition. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Scharmer, Otto (2007). Theory U: Leading from the Future as it Emerges—The Social Technology of Presencing. Cambridge, MA: The Society for Organizational Learning.

Sutherland, Kate (2012). Make Light Work in Groups: 10 Tools to Transform Meetings, Companies and Communities. Vancouver: Incite Press.

Transformative Learning Centre/TLC (2007a) What are dialogue circles? in Schedule, Spirit Matters One Earth Community Gathering website. Retrieved July 22, 2014 from www.legacy.oise.utoronto.ca/research/tlcentre/gathering2007/schedule.html

Transformative Learning Centre/TLC (2007b) in Process, Spirit Matters One Earth Community Gathering website. Retrieved July 22, 2014 from http://legacy.oise.utoronto.ca/research/tlcentre/gathering2007/media.html

Bohm, David (1996). On Dialogue. London and New York: Routledge Classics.

Burkhardt, Vern (2010). Thinking Together, Part 1, IdeaConnection Interview with William Isaacs, Author of Dialogue: The Art of Thinking Together. Retrieved July 20, 2014 from http://www.ideaconnection.com/open-innovation-articles/00172-Thinking-Together-Part-1.html.

Einstein, Albert (1946, May 25). Atomic Education Urged by Einstein. The New York Times.

Gendlin, Eugene T (1992). The Primacy of the Body, Not the Primacy of Perception: How the Body Knows the Situation and Philosophy. Man and World 25.3-4, 341-353.

Hart, Rebekah (2005). Earth Knows, Body Knows: Explorations in the Felt Ecology of an Animate World. Unpublished paper for the McGill School of Environment.

Hubbard, Barbara Marx (1998). Conscious Evolution: Awakening the Power of our Social Potential. San Francisco: New World Library.

Isaacs, William (1999) Dialogue and the Art of Thinking Together. New York: Crown Business.

Jaworski, Joseph (2012). Source: The Inner Path of Knowledge Creation. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Lederach, John Paul (2005). The Moral Imagination: The Art and Soul of Building Peace. Oxford, MA: Oxford University Press.

Macy, Joanna and Young Brown, M (1998). Coming Back to Life: Practices to Reconnect Our Lives, Our World. Gabriola Island, B.C.: New Society Publishers.

Macy, Joanna (n.d.a). Theoretical Foundations, Joanna Macy and Her Work website. Retrieved July 23 2014 from www.joannamacy.net/theworkthatreconnects/theoretical-foundations.html.

Macy, Joanna (n.d.b) Drawing by Dori Midnight, in The Spiral of the Work That Reconnects, Joanna Macy and Her Work website. Retrieved July 23 2014 from http://www.joannamacy.net/theworkthatreconnects/the-wtr-spiral.html. Reproduced with permission.

McPherson, Guy (2013, January 6). Climate-Change Summary and Update. Retrieved July 22 2014 from http://guymcpherson.com/2013/01/climate-change-summary-and-update/.

Owen, Harrison (2008). Open Space Technology: A User’s Guide, 3rd Edition. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Scharmer, Otto (2007). Theory U: Leading from the Future as it Emerges—The Social Technology of Presencing. Cambridge, MA: The Society for Organizational Learning.

Sutherland, Kate (2012). Make Light Work in Groups: 10 Tools to Transform Meetings, Companies and Communities. Vancouver: Incite Press.

Transformative Learning Centre/TLC (2007a) What are dialogue circles? in Schedule, Spirit Matters One Earth Community Gathering website. Retrieved July 22, 2014 from www.legacy.oise.utoronto.ca/research/tlcentre/gathering2007/schedule.html

Transformative Learning Centre/TLC (2007b) in Process, Spirit Matters One Earth Community Gathering website. Retrieved July 22, 2014 from http://legacy.oise.utoronto.ca/research/tlcentre/gathering2007/media.html

Notes

[1] This is often paraphrased as: “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.”

[1] Personal notes taken during the gathering.

[1] Personal notes taken during the gathering.

[1] Personal notes taken during the gathering.

[1] Personal notes taken during the gathering.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed