by Natalie Zend

This essay offers my thoughts on some of what is required for transformative social change. I wrote it in honour of the work of the Transformative Learning/Spirit Matters Community, for inclusion in its book Transformative Learning in the 21st Century: Revisioning Education around the Planet, intended for publication by Zed Books, London, UK, in 2015. Illness within the editorial team has held up publication of the book, but I share the essay here as an expression of one aspect of how I approach changemaking.

Summary

With small but radical gestures—a quiet room for meditation and prayer and guided moments of personal reflection—the Transformative Learning Centre (TLC) has offered socially-sanctioned public spaces to slow down and listen to silence. This is rare in a world so speeded up by the imperatives of technology and the marketplace. That is even more the case among groups dedicated to social change, where the urgency of the issues tends to dictate a frenetic pace. And yet, respect for rest and receptivity is an essential condition for creating a life-sustaining society.

If what we want to achieve is nothing less than a transformation in our societal systems and structures, we need to go slow to go fast. Trying to effect change from the same place of disconnection from the rhythms of life as the system we are trying to change simply will not bring the transformation we seek. Slowing down, being quiet, reflecting and receiving are not just helpful, they are essential for deep change work. This is required for our actions to have integrity and coherence and therefore effectiveness. It is what we need, to keep doing the work. And it is a crucial element in the innovation and creativity necessary to bring about a new kind of human presence on the planet.

Returning to nature’s rhythms and allowing ourselves regular rest and quiet is not an easy shift for most of us agents of change to make. There is just so much to do, if we are to preserve Earth’s life support systems and midwife a new society into being. Everything seems to scream at us, “Don't just sit there, do something!" And with so little time left to turn the tide, it seems that we need to do that something as quickly and relentlessly as possible. Yet the very survival of complex life on Earth depends on our capacity to slow down and listen. Even when we discover this and become convinced of it, changing our inner conditioning is no small challenge. We all need permission to pause. What the TLC has done—creating new social norms that sanction quiet rest and reflection—is ground breaking and important. A new world is on its way, and, like all great music, it will come from silence.

If what we want to achieve is nothing less than a transformation in our societal systems and structures, we need to go slow to go fast. Trying to effect change from the same place of disconnection from the rhythms of life as the system we are trying to change simply will not bring the transformation we seek. Slowing down, being quiet, reflecting and receiving are not just helpful, they are essential for deep change work. This is required for our actions to have integrity and coherence and therefore effectiveness. It is what we need, to keep doing the work. And it is a crucial element in the innovation and creativity necessary to bring about a new kind of human presence on the planet.

Returning to nature’s rhythms and allowing ourselves regular rest and quiet is not an easy shift for most of us agents of change to make. There is just so much to do, if we are to preserve Earth’s life support systems and midwife a new society into being. Everything seems to scream at us, “Don't just sit there, do something!" And with so little time left to turn the tide, it seems that we need to do that something as quickly and relentlessly as possible. Yet the very survival of complex life on Earth depends on our capacity to slow down and listen. Even when we discover this and become convinced of it, changing our inner conditioning is no small challenge. We all need permission to pause. What the TLC has done—creating new social norms that sanction quiet rest and reflection—is ground breaking and important. A new world is on its way, and, like all great music, it will come from silence.

Quiet Space: The Importance of Slowing Down

My first encounter with The Transformative Learning Centre (TLC) in 2007 was nothing less than a watershed in my life and work (see “Dialogue—The Final Frontier”). Subsequent Spirit Matters gatherings offered a further life-saving gift. They gave social validation and space for something rarely honoured in our modern world, especially among change-makers: rest and quiet. The 2010 gathering offered a quiet room for meditation and prayer as an intrinsic part of the event—the first such room I’d ever seen at a conference. And halfway through the 2012 gathering, animators guided us in taking some moments for personal reflection during the conversation cafés.

It would be hard to overstate what these small but radical gestures meant to me. In a world so speeded up by the imperatives of technology and the marketplace—where time is money, and space is money too—socially-sanctioned public spaces to slow down and listen to silence are rare. This is, if anything, even more the case among groups dedicated to social change, where the urgency of the issues tends to dictate a frenetic pace.

The Quiet Room and the facilitated moments of reflection were like finally seeing my deepest longings take shape. In a public, social space, in a gathering of change-makers, and within an academic setting, we were actually being encouraged to pause, to rest, to digest, to enjoy silence and to listen inside. At last I had found a socially-aware, action-oriented community that understood the value of quiet. It didn’t just pay lip service to it. Instead, the TLC has actively created social norms that allow change agents to return to the natural rhythms that keep life going. In so doing, it is adopting an essential condition for creating the just, thriving, sustainable society that is waiting to be born: respect for rest and receptivity.

It would be hard to overstate what these small but radical gestures meant to me. In a world so speeded up by the imperatives of technology and the marketplace—where time is money, and space is money too—socially-sanctioned public spaces to slow down and listen to silence are rare. This is, if anything, even more the case among groups dedicated to social change, where the urgency of the issues tends to dictate a frenetic pace.

The Quiet Room and the facilitated moments of reflection were like finally seeing my deepest longings take shape. In a public, social space, in a gathering of change-makers, and within an academic setting, we were actually being encouraged to pause, to rest, to digest, to enjoy silence and to listen inside. At last I had found a socially-aware, action-oriented community that understood the value of quiet. It didn’t just pay lip service to it. Instead, the TLC has actively created social norms that allow change agents to return to the natural rhythms that keep life going. In so doing, it is adopting an essential condition for creating the just, thriving, sustainable society that is waiting to be born: respect for rest and receptivity.

Natural rhythms and the pressure to override them

In nature, there is a rhythm to everything. Our bodies have rhythms. When we breathe, we exhale, contracting our lungs and sending air out into the world. But were we only to exhale, we would soon expire! Before and after every exhalation, we need to inhale, expanding our lungs and allowing them to take in air from outside our bodies. When our hearts beat, they pump blood through our arteries to the rest of our bodies. But were they only to send the blood out, they would soon fail. Each contraction, or systole, is preceded and succeeded, by a dilatation—the diastole—during which the heart refills with blood. The earth too has rhythms: night follows day, spring and summer give way to fall and winter.

But modern society has learned how to ignore and override these cycles. Time is mechanized and counted by the clock, and therefore experienced as separate from our bodies and from the earth. Time is a liability: you have to pay people for it. Productivity and outputs are the measures of success, and success is measured in very short periods—an economic quarter, a political term, an academic session. From within this worldview, conquering nature’s rhythms is desirable: it helps us do more, faster. With electrical light, we have defeated the night. We no longer need to stop and rest for the dark part of each twenty four-hour cycle. With heating, we have conquered winter: no need for dormancy or hibernation.

As a citizen of this planet-time I feel this pressure to be constantly producing and growing. It operates from patterns planted deep within me by my ancestors, my education, the modeling of peers and the ambient culture. A few years ago I came across a letter that my father wrote to his sister-in-law in 1969. In it, he writes of a series of unprecedented successes in his career, and concludes:

But modern society has learned how to ignore and override these cycles. Time is mechanized and counted by the clock, and therefore experienced as separate from our bodies and from the earth. Time is a liability: you have to pay people for it. Productivity and outputs are the measures of success, and success is measured in very short periods—an economic quarter, a political term, an academic session. From within this worldview, conquering nature’s rhythms is desirable: it helps us do more, faster. With electrical light, we have defeated the night. We no longer need to stop and rest for the dark part of each twenty four-hour cycle. With heating, we have conquered winter: no need for dormancy or hibernation.

As a citizen of this planet-time I feel this pressure to be constantly producing and growing. It operates from patterns planted deep within me by my ancestors, my education, the modeling of peers and the ambient culture. A few years ago I came across a letter that my father wrote to his sister-in-law in 1969. In it, he writes of a series of unprecedented successes in his career, and concludes:

The fact that I am on the rising wave is beautiful, but I shouldn’t sink back to the bottom again. I have to confirm my successes and try to get on top of a higher wave. I have to translate glory to money, invest interest into capital, plow the crop to secure the next bigger harvest.

He wanted forever to stay on the crest of the wave, and avoid the trough. Don’t we all? This is my inheritance. But this is like wanting only ever to exhale—because the world needs what we have to give! Or wanting the heart only ever to pump blood out—because the body needs more oxygen! Four years after writing that letter, my dad had the first of three heart attacks, culminating in an early death.

Because nature simply doesn’t work that way. Without the trough there is no peak. Without the inhalation, there is no exhalation: receiving the air is as necessary as giving it out. There is no systole without diastole: receiving the blood is as important as pumping it out. Sleep is not merely lost time. It is a period of active restoration during which we synthesize proteins, grow muscle, and repair tissues. Plants in temperate zones use winter dormancy to maintain their cell membranes and rebuild their proteins. Many trees and flowers actually need the winter chill to blossom in the spring.

Because nature simply doesn’t work that way. Without the trough there is no peak. Without the inhalation, there is no exhalation: receiving the air is as necessary as giving it out. There is no systole without diastole: receiving the blood is as important as pumping it out. Sleep is not merely lost time. It is a period of active restoration during which we synthesize proteins, grow muscle, and repair tissues. Plants in temperate zones use winter dormancy to maintain their cell membranes and rebuild their proteins. Many trees and flowers actually need the winter chill to blossom in the spring.

Rewriting the story

Why does any of this matter? As humans, don’t we have the privilege of being able to rise above nature? Haven’t we learned to harness nature’s resources toward the development of human culture, civilization and consciousness? Hasn’t our mastery of the elements afforded us incredible advances in science, technology, and human health and well being? These questions all point to a central assumption that underlies our global industrial growth society: that we are separate and can dominate and use our own bodies, other people and the earth. With that assumption we have privileged doing over being, giving over receiving, speaking over listening, outer over inner, mind over matter, masculine over feminine.

But at this epochal turning point, that assumption is being proven wrong, even pathological. The intersecting crises of climate change, mass species extinction, and peak oil, in the context of exponential growth in the human population, have brought us to a brink of time. Since the seventies we have been using more of the planet’s body than what nature can regenerate. As Susan Burns, CEO of the Global Footprint Network, says, “humanity is living off of its ecological credit card. If we use more than nature can keep up with, we start to erode the natural capital that our life depends on.” (Generation Waking Up, 2013: 43) As a result, our current growth-based civilization is not sustainable, and so it will not last. But beyond that, what hangs in the balance is nothing less than the continuation of complex life on Earth.

Now is the moment to rewrite the script that has brought us to this precipice, to flip the assumption that runs through our narrative. The time has come to reclaim the innate wisdom that resides in our bodies. Our lungs know that inhale and exhale are equally important. Our hearts know that diastole and systole are inseparable. Our gonads know that both feminine and masculine are needed for creation. They tell us that being and doing, receiving and giving, listening and speaking, wakefulness and sleep, are also alternating moments that allow life to flow through us. Walking is easier when the right and left foot follow one another. In the same way, each of these dualities is interdependent and complementary, and together forms an indivisible whole. Taoism expresses this principle as the dynamic interconnectedness of yin, the female, receptive principle, and yang, the male, active principle, that together form the tao—literally, “the way the universe works.” As the Chinese saying goes, “the circle of wholeness is made up of action and stillness.” (quoted in Berkana, 2012)

But at this epochal turning point, that assumption is being proven wrong, even pathological. The intersecting crises of climate change, mass species extinction, and peak oil, in the context of exponential growth in the human population, have brought us to a brink of time. Since the seventies we have been using more of the planet’s body than what nature can regenerate. As Susan Burns, CEO of the Global Footprint Network, says, “humanity is living off of its ecological credit card. If we use more than nature can keep up with, we start to erode the natural capital that our life depends on.” (Generation Waking Up, 2013: 43) As a result, our current growth-based civilization is not sustainable, and so it will not last. But beyond that, what hangs in the balance is nothing less than the continuation of complex life on Earth.

Now is the moment to rewrite the script that has brought us to this precipice, to flip the assumption that runs through our narrative. The time has come to reclaim the innate wisdom that resides in our bodies. Our lungs know that inhale and exhale are equally important. Our hearts know that diastole and systole are inseparable. Our gonads know that both feminine and masculine are needed for creation. They tell us that being and doing, receiving and giving, listening and speaking, wakefulness and sleep, are also alternating moments that allow life to flow through us. Walking is easier when the right and left foot follow one another. In the same way, each of these dualities is interdependent and complementary, and together forms an indivisible whole. Taoism expresses this principle as the dynamic interconnectedness of yin, the female, receptive principle, and yang, the male, active principle, that together form the tao—literally, “the way the universe works.” As the Chinese saying goes, “the circle of wholeness is made up of action and stillness.” (quoted in Berkana, 2012)

Go slow to go fast

As agents of change wanting to co-create a more peaceful, equitable, and sustainable way of life, it is especially vital that we come to have faith in the natural alternation of these dualities. Even more than that, we need to counteract centuries of exclusive valuing of production and growth and actually focus our attention on stopping, resting and receiving. If we do, experience will show us that life-giving action naturally follows. We make less effort, but achieve more, because we are engaging with the flow of life rather than pushing the river.

This isn’t easy. As eco-philosopher Joanna Macy says, “to intervene in the political and legislative decisions of the Industrial Growth Society, we fall by necessity into its tempo. We race to find and pull the levers before it is too late to save this forest, or stop that weapons program.” (Macy and Brown, 1998: 136) In my work with human rights and social justice organizations, time and again I have seen how strong is the drive to do more, faster, better. Working relentless long hours and sleeping little has become a kind of badge of honour in many organizational cultures. Setting one’s own needs aside for the benefit of the group or community is seen as a sought-after skill, because the world is in crisis and we need to save it. Diminishing financial resources and reduced staff only heighten the pressure to constantly move, act and do.

But if what we want to achieve is nothing less than a sea-change in our societal systems and structures, we need to go slow to go fast. Trying to effect change from the same place of disconnection from the rhythms of life as the system we are trying to change simply will not bring the transformation we seek. Slowing down, being quiet, reflecting and receiving are not just helpful, they are essential for deep change work. This is required for our actions to have integrity and coherence and therefore effectiveness. It is what we need to keep doing the work. And it is a crucial element in the innovation and creativity necessary to bring about a new kind of human presence on the planet.

This isn’t easy. As eco-philosopher Joanna Macy says, “to intervene in the political and legislative decisions of the Industrial Growth Society, we fall by necessity into its tempo. We race to find and pull the levers before it is too late to save this forest, or stop that weapons program.” (Macy and Brown, 1998: 136) In my work with human rights and social justice organizations, time and again I have seen how strong is the drive to do more, faster, better. Working relentless long hours and sleeping little has become a kind of badge of honour in many organizational cultures. Setting one’s own needs aside for the benefit of the group or community is seen as a sought-after skill, because the world is in crisis and we need to save it. Diminishing financial resources and reduced staff only heighten the pressure to constantly move, act and do.

But if what we want to achieve is nothing less than a sea-change in our societal systems and structures, we need to go slow to go fast. Trying to effect change from the same place of disconnection from the rhythms of life as the system we are trying to change simply will not bring the transformation we seek. Slowing down, being quiet, reflecting and receiving are not just helpful, they are essential for deep change work. This is required for our actions to have integrity and coherence and therefore effectiveness. It is what we need to keep doing the work. And it is a crucial element in the innovation and creativity necessary to bring about a new kind of human presence on the planet.

To give something, you have to have it

If we want to create a sustainable world, we need to work in a sustainable way. To paraphrase engaged Zen Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh, to give something, first you have to have it. How can you give something you do not have? We want to create sustainability, and in the seeming urgency of the crisis we are constantly acting and moving, rushing to make the world a better place. In so doing, we end up using more of our body’s resources than it can replenish, living off of our biological credit card, and in too many cases, burning out. In the very effort to change what we are collectively doing to the body of the planet, we are treating our own bodies in just the same way. If we want to bring sustainability into the world, we need to really know what it is, from the inside out. We need to do it in a deep way, all the way through.

Likewise, if we want to bring about justice, we need to be just in the way we work. In one human rights organization with which I worked, a colleague once commented to me, “This is the one job I’ve had where my rights as a worker have been least respected.” We were working fifteen-hour days for what amounted to about $12 an hour. But this was more a self-compliment than a complaint: the internal culture was to see the non-profit’s mission as a worthy cause for personal sacrifice. In the end, such paradoxical norms model and promote injustice, creating an arguably exploitative dynamic. Funders and the organization produced impressive results at very low cost thanks to the martyr-like devotion of many volunteers and underpaid workers. In its way of working, the organization was ultimately conceding to and reinforcing an unfair distribution of wealth, where work with little social value (such as manufacturing weapons or distributing pornography) is vastly more rewarded than work that makes a genuine contribution to well-being.

What we are and what we do are our greatest teachings and contributions; what we say a very distant second. How can we truly spread justice and sustainability unless we are embodying those qualities and becoming vehicles for their realization in the world? The saviour complex so prevalent among change-makers may at first blush seem like great fuel for our work. But in the end, self-sacrifice can do more to inflate our egos than to actually manifest the values we stand for.

Likewise, if we want to bring about justice, we need to be just in the way we work. In one human rights organization with which I worked, a colleague once commented to me, “This is the one job I’ve had where my rights as a worker have been least respected.” We were working fifteen-hour days for what amounted to about $12 an hour. But this was more a self-compliment than a complaint: the internal culture was to see the non-profit’s mission as a worthy cause for personal sacrifice. In the end, such paradoxical norms model and promote injustice, creating an arguably exploitative dynamic. Funders and the organization produced impressive results at very low cost thanks to the martyr-like devotion of many volunteers and underpaid workers. In its way of working, the organization was ultimately conceding to and reinforcing an unfair distribution of wealth, where work with little social value (such as manufacturing weapons or distributing pornography) is vastly more rewarded than work that makes a genuine contribution to well-being.

What we are and what we do are our greatest teachings and contributions; what we say a very distant second. How can we truly spread justice and sustainability unless we are embodying those qualities and becoming vehicles for their realization in the world? The saviour complex so prevalent among change-makers may at first blush seem like great fuel for our work. But in the end, self-sacrifice can do more to inflate our egos than to actually manifest the values we stand for.

Because it is the natural order, it will be sustained

At a more prosaic level, to quote Dr. Larry Nusbaum, M.D. in a conversation we had in 2009, self-care is simple physics. If we want to keep doing this work, we need to meet our own needs first. In an airplane, the safety instructions always say that if you are traveling with someone who requires assistance, put on your own oxygen mask first. Then assist the other person. If you can’t breathe, what good are you to anyone else? The first port of call is necessarily yourself. And from an organizational perspective, it is simply good management to fuel the mule.

Our relentless focus on productivity is like constantly drawing as much water as possible from a well. An overdrawn well can become cut off from its source, the underground stream that feeds it. Its water can turn stagnant and toxic. Ultimately the well might become depleted and dry up. In the same way, if we focus only on drawing from the well of our energy and creativity, without stopping and opening to the source, what we produce can be a needlessly diminished version of its full potential. As twelfth century philosopher and mystic Hildegard of Bingen wrote, “the greatest sin in life is to dry up.” (in Robertson, 2013: 27)

In over-emphasizing doing, we are like a tree that focuses exclusively on producing large and numerous fruit, but neglects to grow its roots deep into the ground. Such a tree will be precarious and easily toppled. Ultimately, it will lack the nourishment needed to produce the fruit. In the literal sense of the word “radical,” pertaining to the root, rest is therefore radical: it takes us to the source. In times of crisis, the best way we can serve is perhaps to be, as leadership educator Michael Jones puts it, “deeply rooted to the subtle forces within ourselves.” (2014: 137)

During Israel’s recent third intifada, I witnessed a conversation with Israeli psychologist and peacemaker Dr. Yitzhak Mendelsohn. When asked what his next steps would be, he answered, “I don’t know. I simply stay in the practices that help me stay in the heart.” In times of turmoil and collapse, perhaps the greatest contribution is to bring love and not fear to the world—as he put it, “to manage fear so fear doesn’t manage our lives.” To be of true service, we need to be present to what’’s happening, and for that, regular rest and quiet are essential.

When we realize this, every conference and workplace dedicated to social change will have a quiet room: inclusive, full of beauty, and tended with care. Moments of silence or quiet personal reflection will be built into every class and staff meeting. Nap rooms will be the rage not only among leading companies, but among social enterprises, non-profits, grassroots groups, and educational institutions. We will reclaim rest and quiet, and because that is the natural order, we will be sustained.

Our relentless focus on productivity is like constantly drawing as much water as possible from a well. An overdrawn well can become cut off from its source, the underground stream that feeds it. Its water can turn stagnant and toxic. Ultimately the well might become depleted and dry up. In the same way, if we focus only on drawing from the well of our energy and creativity, without stopping and opening to the source, what we produce can be a needlessly diminished version of its full potential. As twelfth century philosopher and mystic Hildegard of Bingen wrote, “the greatest sin in life is to dry up.” (in Robertson, 2013: 27)

In over-emphasizing doing, we are like a tree that focuses exclusively on producing large and numerous fruit, but neglects to grow its roots deep into the ground. Such a tree will be precarious and easily toppled. Ultimately, it will lack the nourishment needed to produce the fruit. In the literal sense of the word “radical,” pertaining to the root, rest is therefore radical: it takes us to the source. In times of crisis, the best way we can serve is perhaps to be, as leadership educator Michael Jones puts it, “deeply rooted to the subtle forces within ourselves.” (2014: 137)

During Israel’s recent third intifada, I witnessed a conversation with Israeli psychologist and peacemaker Dr. Yitzhak Mendelsohn. When asked what his next steps would be, he answered, “I don’t know. I simply stay in the practices that help me stay in the heart.” In times of turmoil and collapse, perhaps the greatest contribution is to bring love and not fear to the world—as he put it, “to manage fear so fear doesn’t manage our lives.” To be of true service, we need to be present to what’’s happening, and for that, regular rest and quiet are essential.

When we realize this, every conference and workplace dedicated to social change will have a quiet room: inclusive, full of beauty, and tended with care. Moments of silence or quiet personal reflection will be built into every class and staff meeting. Nap rooms will be the rage not only among leading companies, but among social enterprises, non-profits, grassroots groups, and educational institutions. We will reclaim rest and quiet, and because that is the natural order, we will be sustained.

Slowing down to innovate the future we want

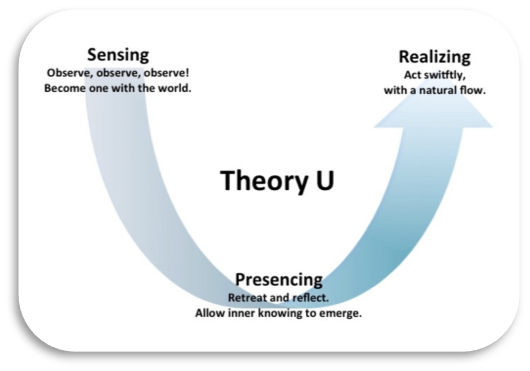

In overriding the natural rhythms of life and their phases of rest and receptivity, we lose connection not only to the basic mechanisms that keep us going. We also lose access to the wisdom and creativity that we need to innovate new social structures, systems and processes that will allow us to sustain and regenerate life on Earth. Most learning methods are based on the experiential learning cycle elaborated by Kurt Lewin, David Kolb and Edgar Schein: experience, reflection, generalization and application. They help us learn from the past. But an even more vital type of learning in this precarious planet-time is what MIT’s Otto Scharmer calls “learning from the future as it emerges.” (2009)

This is the kind of learning we see among innovators, inventors, artists and creative people of all kinds. It is learning that accesses what physicist and philosopher David Bohm called the “implicate order,” a creative source of infinite potential. From that source, it unfolds the “explicate order,” or manifest universe. (1996) Scharmer and his colleagues have interviewed hundreds of practitioners and thought leaders on innovation, and developed the U Theory to show how this type of learning happens. The bottom of the U is where source, or the implicate order, is accessed, and a deeper level of knowing is allowed to emerge. This is the kind of knowing that comes not from what we have learned from experience—our own or that of our parents, teachers, or the experts. It is the kind of knowing that comes when we master not knowing. It comes when we tap into the as-yet unmanifest realm, the field of all potential. It comes not through our brains, but through our hearts, our guts, our bodies. If there’s any method for us to innovate alternatives to the systems and structures that have brought us to the edge of catastrophe at which our civilization now teeters, this is it.

This is the kind of learning we see among innovators, inventors, artists and creative people of all kinds. It is learning that accesses what physicist and philosopher David Bohm called the “implicate order,” a creative source of infinite potential. From that source, it unfolds the “explicate order,” or manifest universe. (1996) Scharmer and his colleagues have interviewed hundreds of practitioners and thought leaders on innovation, and developed the U Theory to show how this type of learning happens. The bottom of the U is where source, or the implicate order, is accessed, and a deeper level of knowing is allowed to emerge. This is the kind of knowing that comes not from what we have learned from experience—our own or that of our parents, teachers, or the experts. It is the kind of knowing that comes when we master not knowing. It comes when we tap into the as-yet unmanifest realm, the field of all potential. It comes not through our brains, but through our hearts, our guts, our bodies. If there’s any method for us to innovate alternatives to the systems and structures that have brought us to the edge of catastrophe at which our civilization now teeters, this is it.

And for this type of learning, quiet and rest are a necessity. Going down the left side of the U requires us to slow down. At the bottom of the U, says complexity scientist Brian Arthur, “the insight arrives not in the midst of activities or frenzied thought, but in moments of stillness.” (quoted in Jaworski, 2012: 150). To receive such inspiration requires one to “retreat and reflect.” (Scharmer: 33, see image to the left) As Thomas Edison’s wife said of her husband, the man who invented the phonograph, the motion picture camera, and the electric light bulb, “he believes that his inventions come through him from the infinite forces of the Universe—and never so well as when he is relaxed.” (quoted in Jaworski: 150)

As Dr. Mendelsohn underlines, out of fear, anxiety and tension we run too fast to act, rushing to respond to a sense of crisis without really knowing what is appropriate to do. This type of learning is a process not of seeking for solutions and driving toward the future, but of stopping, acknowledging that we don’t know, opening, listening, and allowing the knowing to emerge. And such stillness and relaxation require “places and cocoons of deep reflection and silence,” as Scharmer puts it. They ask that organizations establish infrastructures “that facilitate deep listening and connection to the source of authentic presence and creativity, both individually and collectively.” (44) We may fear that slowing down in this way will waste time and money and slow us down in our change efforts. But just the opposite is true: the clarity that emerges at the bottom of the U allows an acceleration as we “act in an instant,” moving into swift action that follows nature’s momentum and acts on nature’s behalf.

Returning to nature’s rhythms and allowing ourselves regular rest and quiet is not an easy shift for most of us agents of change to make. There is just so much to do, if we are to preserve Earth’s life support systems and midwife a new society into being. Everything seems to scream at us, “Don't just sit there, do something!" And with so little time left to turn the tide, it seems that we need to do that something as quickly and relentlessly as possible.

I’ve posited here that sometimes the opposite is more helpful. As Thich Nhat Hanh says, “Don’t just do something, sit there!” (1991) The very survival of complex life on Earth depends on it. Yet even when we discover this and become convinced of it, changing our inner conditioning is no small challenge. After years of retraining myself to regularly stop, sit, breathe, listen, and allow, I still catch myself pushing through and overriding the need for rest. Sometimes I glimpse the deep unconscious messages that drive me—beliefs like, “the more you do, the more you matter,” and “the busier you are, the more you’re worth.” I know I’m not alone in this: we all need permission to pause. What the TLC has done—creating new social norms that sanction quiet rest and reflection—is ground-breaking and important. A new world is on its way, and, like all great music, it will come from silence.

As Dr. Mendelsohn underlines, out of fear, anxiety and tension we run too fast to act, rushing to respond to a sense of crisis without really knowing what is appropriate to do. This type of learning is a process not of seeking for solutions and driving toward the future, but of stopping, acknowledging that we don’t know, opening, listening, and allowing the knowing to emerge. And such stillness and relaxation require “places and cocoons of deep reflection and silence,” as Scharmer puts it. They ask that organizations establish infrastructures “that facilitate deep listening and connection to the source of authentic presence and creativity, both individually and collectively.” (44) We may fear that slowing down in this way will waste time and money and slow us down in our change efforts. But just the opposite is true: the clarity that emerges at the bottom of the U allows an acceleration as we “act in an instant,” moving into swift action that follows nature’s momentum and acts on nature’s behalf.

Returning to nature’s rhythms and allowing ourselves regular rest and quiet is not an easy shift for most of us agents of change to make. There is just so much to do, if we are to preserve Earth’s life support systems and midwife a new society into being. Everything seems to scream at us, “Don't just sit there, do something!" And with so little time left to turn the tide, it seems that we need to do that something as quickly and relentlessly as possible.

I’ve posited here that sometimes the opposite is more helpful. As Thich Nhat Hanh says, “Don’t just do something, sit there!” (1991) The very survival of complex life on Earth depends on it. Yet even when we discover this and become convinced of it, changing our inner conditioning is no small challenge. After years of retraining myself to regularly stop, sit, breathe, listen, and allow, I still catch myself pushing through and overriding the need for rest. Sometimes I glimpse the deep unconscious messages that drive me—beliefs like, “the more you do, the more you matter,” and “the busier you are, the more you’re worth.” I know I’m not alone in this: we all need permission to pause. What the TLC has done—creating new social norms that sanction quiet rest and reflection—is ground-breaking and important. A new world is on its way, and, like all great music, it will come from silence.

References

Bohm, David (1996). On Dialogue. London and New York: Routledge Classics.

Dunford, Aerin (2012). “Berkana Steps into a Bold Experiment in Living Systems,” The Berkana Institute Blog, retrieved October 10 2014 from http://berkana.org/2012/03/berkana-steps-into-a-bold-experiment-in-living-systems/

Generation Waking Up (2013, July). The Generation Waking Up Toolkit, Version 2.1. Retreived October 10 2014 from http://generationwakingup.org/programs/wakeup/resources

Jaworski, Joseph (2012). Source: The Inner Path of Knowledge Creation. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Jones, Michael (2014). The Soul of Place: Re-imagining Leadership Through Nature, Art and Community. Victoria, B.C.: Friesen Press.

Nhat Hanh, Thich (1991). Peace is Every Step: The Path of Mindfulness in Everyday Life. New York: Bantam Books. Quote retrieved on October 10, 2014 from http://www.livinglifefully.com/flo/floaimlessness.htm

Robertson, Randall (2013, January). “Lead an Awe-Inspired Life: Matthew Fox Shares Insights on Creativity and the Divine,” Natural Awakenings Magazine. Retrieved October 11 2014 from http://issuu.com/gonaturalawakenings/docs/january2013naturalawakeningsonline/27

Scharmer, Otto (2007). Theory U: Leading from the Future as it Emerges—The Social Technology of Presencing. Cambridge, MA: The Society for Organizational Learning.

Sherman, Paul (n.d.). Yin Yang Tree. For WPClipart, Public Domain. Retrieved October 20 2014 from http://narutofanon.wikia.com/wiki/File:Yin_yang_tree.png

Dunford, Aerin (2012). “Berkana Steps into a Bold Experiment in Living Systems,” The Berkana Institute Blog, retrieved October 10 2014 from http://berkana.org/2012/03/berkana-steps-into-a-bold-experiment-in-living-systems/

Generation Waking Up (2013, July). The Generation Waking Up Toolkit, Version 2.1. Retreived October 10 2014 from http://generationwakingup.org/programs/wakeup/resources

Jaworski, Joseph (2012). Source: The Inner Path of Knowledge Creation. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Jones, Michael (2014). The Soul of Place: Re-imagining Leadership Through Nature, Art and Community. Victoria, B.C.: Friesen Press.

Nhat Hanh, Thich (1991). Peace is Every Step: The Path of Mindfulness in Everyday Life. New York: Bantam Books. Quote retrieved on October 10, 2014 from http://www.livinglifefully.com/flo/floaimlessness.htm

Robertson, Randall (2013, January). “Lead an Awe-Inspired Life: Matthew Fox Shares Insights on Creativity and the Divine,” Natural Awakenings Magazine. Retrieved October 11 2014 from http://issuu.com/gonaturalawakenings/docs/january2013naturalawakeningsonline/27

Scharmer, Otto (2007). Theory U: Leading from the Future as it Emerges—The Social Technology of Presencing. Cambridge, MA: The Society for Organizational Learning.

Sherman, Paul (n.d.). Yin Yang Tree. For WPClipart, Public Domain. Retrieved October 20 2014 from http://narutofanon.wikia.com/wiki/File:Yin_yang_tree.png

RSS Feed

RSS Feed