by Natalie Zend

This essay outlines my vision for international development in this planet-time. I wrote it in honour of the work of the Transformative Learning/Spirit Matters Community, for inclusion in its book Transformative Learning in the 21st Century: Revisioning Education around the Planet, intended for publication by Zed Books, London, UK, in 2015. Illness within the editorial team has held up publication of the book, but I share the essay here as an expression of the vision that underpins my community and international development work.

Summary:

I present here a reframing of the field of international development in which I work. I examine what it is that “international development” has been developing, and how that differs from what these times are calling for—something I call “reverse development.”

In essence, international development has been developing a globalized and monetized economy. It has been converting people, other living beings and the planet into commodities that can be bought, used and discarded across large distances. This kind of development is cannibalistic and ultimately suicidal, as we eat and spit out the foundations for life until there is not enough left to sustain us. The basic premise of international development—that “developing” countries need to develop what the “developed” countries have—seems fatally misguided. Instead, we need to reverse our understanding of development so that it aims not to convert nature into money, but to sustain and regenerate life.

We also need to reverse the flow of learning and support, acknowledging that on a number of levels the “developed” world actually needs what the “developing” world has at least as much as the other way around. A number of emerging social movements are inviting those of us in industrialized parts of the world to live better while using less of the Earth’s material and energy. Meanwhile, those in “less developed” parts of the world already have many of the attributes that these movements aim to cultivate among those of us in the “developed” world. For example, indigenous peoples are recovering and lifting their principles and practices up onto the world stage, in so doing offering values and possibilities that all of humanity needs at this time.

Ultimately, “reverse development” is about humility and courage in the face of an uncertain future. It is about calling upon the widest, wildest and wisest humanity in people in both the “developing” and “developed” parts of the planet. Everyone brings a vital element; nobody has the solutions. It is also about humility in the face of another. It is about dropping our notions of teacher and taught, “developer” and “developing,” and coming together as partners and collaborators. The Transformative Learning Centre (TLC) has done a remarkable job of elevating the knowledge and wisdom of those whom the mainstream development paradigm would assume to be in need of development and learning. It gathers us in from all directions as friends and colleagues to learn alongside one another.

In essence, international development has been developing a globalized and monetized economy. It has been converting people, other living beings and the planet into commodities that can be bought, used and discarded across large distances. This kind of development is cannibalistic and ultimately suicidal, as we eat and spit out the foundations for life until there is not enough left to sustain us. The basic premise of international development—that “developing” countries need to develop what the “developed” countries have—seems fatally misguided. Instead, we need to reverse our understanding of development so that it aims not to convert nature into money, but to sustain and regenerate life.

We also need to reverse the flow of learning and support, acknowledging that on a number of levels the “developed” world actually needs what the “developing” world has at least as much as the other way around. A number of emerging social movements are inviting those of us in industrialized parts of the world to live better while using less of the Earth’s material and energy. Meanwhile, those in “less developed” parts of the world already have many of the attributes that these movements aim to cultivate among those of us in the “developed” world. For example, indigenous peoples are recovering and lifting their principles and practices up onto the world stage, in so doing offering values and possibilities that all of humanity needs at this time.

Ultimately, “reverse development” is about humility and courage in the face of an uncertain future. It is about calling upon the widest, wildest and wisest humanity in people in both the “developing” and “developed” parts of the planet. Everyone brings a vital element; nobody has the solutions. It is also about humility in the face of another. It is about dropping our notions of teacher and taught, “developer” and “developing,” and coming together as partners and collaborators. The Transformative Learning Centre (TLC) has done a remarkable job of elevating the knowledge and wisdom of those whom the mainstream development paradigm would assume to be in need of development and learning. It gathers us in from all directions as friends and colleagues to learn alongside one another.

Reverse Development: Toward a One Earth Community

My first encounter with the Transformative Learning Centre (TLC) was at the “One Earth Community” conference in 2007. My focus there was on the event’s process more than its substance. So much so that it literally took me years to understand just how seminal the content was in its own right. That gathering marked the beginning of a shift not only in the role I play through my work (see “Dialogue—The Final Frontier”), and in the way I work (see “Quiet Space and the Importance of Slowing Down”). It also sowed the seeds of a sea change in my understanding of the international development field in which I’ve been employed since 1997.

It is only now, over seven years later, that I am realizing that my current take on international development—a paradigm I have been calling “reverse development”—was set forth in its bare bones in the TLC’s 2007 gathering call. That Spirit Matters conference focused on “developing a new vision and set of practices for an Earth Community.” Its theme statement said:

It is only now, over seven years later, that I am realizing that my current take on international development—a paradigm I have been calling “reverse development”—was set forth in its bare bones in the TLC’s 2007 gathering call. That Spirit Matters conference focused on “developing a new vision and set of practices for an Earth Community.” Its theme statement said:

We are now becoming aware that the dominating western scale of progress and development is not tuned to human scale nor for that matter to the scale of the Earth. Our task must be to deepen our understanding of development in a manner that takes a much wider spectrum of more-than-human needs into account. In other words, we need to move beyond survival and/or critique into some vivid, creative de-colonizing that calls forth transformative vision and action. We need rekindling of relationship between the human and the natural world that is far beyond the exploitative relationships of our current transnational global market economy. A different kind of prosperity and progress needs to be envisioned which embraces the whole life community.

After ten years in the world of mainstream development, working with Canada’s international aid agency, this invitation was perhaps more than I could fully absorb on a conscious level. It would take a fateful evening almost a year later for me even to begin to wake up to a new view of the waters in which I had been swimming for so long. And years of further exploration and reflection would pass before I would be able fully to seize the vast and very real possibility laid out by that TLC call. Only now do I realize that that call, and the calling it has become for me, is not just about process, but also about ultimate purpose.

The three sights

One evening in 2008 I was taking a stroll down a village road in India. As I walked, I first saw a woman stirring a potful of dinner with a smile on her face. Her teenaged son and daughter were close by, playfully chasing and tagging each other and breaking out in peals of laughter.

I continued walking along the riverside path. Suddenly, a man on a bicycle veered around a corner toward me. As he pedaled past me, I heard him singing gleefully at full volume.

I kept on ambling along. And there, by the side of the road, I saw a sadhu in orange robes, sitting quietly in meditation.

I continued to walk for a few minutes. Then a wave of emotion washed over me, the force of it compelling me to sit down. It was then that I realized that these villagers had shown me, one after the other: connection, joy, and peace.

I knew that my decade of work in international development was rooted in intentions to contribute to good, share the wealth, and save the world. But in that moment I realized that perhaps an even deeper truth was that I went to “underdeveloped” and “impoverished” parts of the world because I needed what they had—and not the other way around. True, this was India and I was not here for work. But I recognized these feelings of aliveness and belonging from communities in South America and Africa where I had traveled for work.

I continued walking along the riverside path. Suddenly, a man on a bicycle veered around a corner toward me. As he pedaled past me, I heard him singing gleefully at full volume.

I kept on ambling along. And there, by the side of the road, I saw a sadhu in orange robes, sitting quietly in meditation.

I continued to walk for a few minutes. Then a wave of emotion washed over me, the force of it compelling me to sit down. It was then that I realized that these villagers had shown me, one after the other: connection, joy, and peace.

I knew that my decade of work in international development was rooted in intentions to contribute to good, share the wealth, and save the world. But in that moment I realized that perhaps an even deeper truth was that I went to “underdeveloped” and “impoverished” parts of the world because I needed what they had—and not the other way around. True, this was India and I was not here for work. But I recognized these feelings of aliveness and belonging from communities in South America and Africa where I had traveled for work.

Converting life into money, growing monoculture

That fateful night flipped my conception of international development on its head. What exactly was it that I was helping to develop in other parts of the world? Connection? Joy? Peace? Aliveness? Belonging in the community of life? No. That is what my time in those “developing” places were helping me to develop. So what was being developed? The broad agenda of international development, and the larger enterprise within which even the most progressive and human rights-based development efforts take place, is what Charles Eisenstein calls the “conversion of life and the world into money, the progressive commodification of everything.” (2011: 30)

You may recognize that well-worn plea for charity: “these people are living on just one dollar a day!” But that often simply means that they are still largely meeting their needs outside of the global money economy. They do that by stewarding land, plants and animals to create clothing, food and shelter, and engaging in mutual exchanges with others. Development, as Eisenstein puts it, is about “bringing [such] nonmonetary economic activity into the realm of goods and services.” Once they’ve been integrated into the globalized industrial cash economy, these same people may have well over a dollar a day but now can scarcely clothe, house or feed themselves. What they do have, on the other hand, is the “mentality of scarcity, competition, and anxiety so familiar to us in the West, yet so alien to the moneyless hunter-gatherer or subsistence peasant.” (Eisenstein, 2011: 30)

In short, international development develops a globalized and monetized economy. It converts people, other living beings and the planet into commodities that can be bought, used and discarded across large distances. Former “economic hit man” John Perkins describes how development loans have been used as instruments for progressively expanding the reach of industrial growth civilization. International financial institutions provide countries with loans to develop infrastructure—on the condition that companies from the “developed” world are the ones to build it. The creditors also require changes in economic policy that increase the debtor countries’ reliance on the rest of the world to meet the needs of their people. Then they make them pay it all back with interest. If these countries default on those payments, the “developed” world demands other forms of payback that further integrate them into the global industrial complex—such as the installation of military bases or access to resources like oil or the Panama Canal. (2004: 1)

This is the endgame in a journey that began with the agricultural revolution over ten thousand years ago, a story that Daniel Quinn engagingly tells in the Ishmael trilogy. (1992, 1996, 1997) Its plotline is that civilized societies continually take over the habitat of other peoples and species, progressively annihilating or assimilating them in the process. Before that—for 99.5 per cent of the three million years of human existence—we were all members of tribal cultures. Like other species, we lived within a self-sustaining balance in which no one organism monopolized the means to sustain life. (Wright, 2004: 14) Now fewer than 5% of humans continue to live in that way. (Hall and Patrinos, 2012: 10) The majority of us are part of an ever-growing monoculture in which food and other life necessities are kept under lock and key, controlled through hierarchical structures, and concentrated in the hands of a few.

Development aid makes it look like rich countries are generously offering charity to their poor neighbours. The bigger picture, however, is actually that developing countries as a group provide a net transfer of financial resources to developed countries (United Nations, 2011: 69). Yes, you read that right. For every $1 developing countries gain, they lose more than $2 (see figure 1). This is perhaps less surprising when you consider that, by definition, “developing” countries are the ones that have more people and more planet yet to convert into monetized goods and services, and the new money thereby created mainly flows to the “developed” countries.

You may recognize that well-worn plea for charity: “these people are living on just one dollar a day!” But that often simply means that they are still largely meeting their needs outside of the global money economy. They do that by stewarding land, plants and animals to create clothing, food and shelter, and engaging in mutual exchanges with others. Development, as Eisenstein puts it, is about “bringing [such] nonmonetary economic activity into the realm of goods and services.” Once they’ve been integrated into the globalized industrial cash economy, these same people may have well over a dollar a day but now can scarcely clothe, house or feed themselves. What they do have, on the other hand, is the “mentality of scarcity, competition, and anxiety so familiar to us in the West, yet so alien to the moneyless hunter-gatherer or subsistence peasant.” (Eisenstein, 2011: 30)

In short, international development develops a globalized and monetized economy. It converts people, other living beings and the planet into commodities that can be bought, used and discarded across large distances. Former “economic hit man” John Perkins describes how development loans have been used as instruments for progressively expanding the reach of industrial growth civilization. International financial institutions provide countries with loans to develop infrastructure—on the condition that companies from the “developed” world are the ones to build it. The creditors also require changes in economic policy that increase the debtor countries’ reliance on the rest of the world to meet the needs of their people. Then they make them pay it all back with interest. If these countries default on those payments, the “developed” world demands other forms of payback that further integrate them into the global industrial complex—such as the installation of military bases or access to resources like oil or the Panama Canal. (2004: 1)

This is the endgame in a journey that began with the agricultural revolution over ten thousand years ago, a story that Daniel Quinn engagingly tells in the Ishmael trilogy. (1992, 1996, 1997) Its plotline is that civilized societies continually take over the habitat of other peoples and species, progressively annihilating or assimilating them in the process. Before that—for 99.5 per cent of the three million years of human existence—we were all members of tribal cultures. Like other species, we lived within a self-sustaining balance in which no one organism monopolized the means to sustain life. (Wright, 2004: 14) Now fewer than 5% of humans continue to live in that way. (Hall and Patrinos, 2012: 10) The majority of us are part of an ever-growing monoculture in which food and other life necessities are kept under lock and key, controlled through hierarchical structures, and concentrated in the hands of a few.

Development aid makes it look like rich countries are generously offering charity to their poor neighbours. The bigger picture, however, is actually that developing countries as a group provide a net transfer of financial resources to developed countries (United Nations, 2011: 69). Yes, you read that right. For every $1 developing countries gain, they lose more than $2 (see figure 1). This is perhaps less surprising when you consider that, by definition, “developing” countries are the ones that have more people and more planet yet to convert into monetized goods and services, and the new money thereby created mainly flows to the “developed” countries.

Beyond the limits, trending toward collapse

This kind of development is cannibalistic and ultimately suicidal, as we eat and spit out the foundations for life until there is not enough left to sustain us. Humanity as a whole, living as we do now, needs one and a half Earths to carry us into the future. (Global Footprint Network, 2014) That means that (based on 2007 data), it takes Earth a year and six months to absorb the waste and regenerate the energy, land, trees, and food that humans use in a year. We have been in ecological overshoot since the early 1970s, and we continue to develop our techno-industrial society by—to put it bluntly—liquidating the Earth. In those forty-odd years, for example, the number of individual vertebrates (mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and fish) with whom we share our planet has fallen by half. (WWF, 2014: 16)

Beyond the Limits, the 20-year update to the renowned 1972 book Limits to Growth, concluded:

Beyond the Limits, the 20-year update to the renowned 1972 book Limits to Growth, concluded:

Human use of many essential resources and generation of many kinds of pollutants have already surpassed rates that are physically sustainable. Without significant reductions in material and energy flows, there will be in the coming decades an uncontrolled decline in per capita food output, energy use, and industrial production. (Meadows, Meadows and Randers: 1992: xv)

Were such a scenario to play out, it would by no means be the first time in the ten thousand year history of human civilization that overshoot led to collapse.

In fact, one after another—Sumer, Rome, Classic Period Maya, Easter Island—civilizations have “robb[ed] the future to pay the present, spending the last reserves of natural capital on a reckless binge of excessive wealth and glory.” (Wright, 2004: 79) The main difference now is that while their populations were geographically confined and never surpassed a hundred million, modern civilization spans the entire globe and we number seven billion. The Easter Islanders made a barren desert of their island. We are following their example. But this time the whole planet is our island, and what’s at stake is nothing less than the very survival of complex life on Earth.

In fact, one after another—Sumer, Rome, Classic Period Maya, Easter Island—civilizations have “robb[ed] the future to pay the present, spending the last reserves of natural capital on a reckless binge of excessive wealth and glory.” (Wright, 2004: 79) The main difference now is that while their populations were geographically confined and never surpassed a hundred million, modern civilization spans the entire globe and we number seven billion. The Easter Islanders made a barren desert of their island. We are following their example. But this time the whole planet is our island, and what’s at stake is nothing less than the very survival of complex life on Earth.

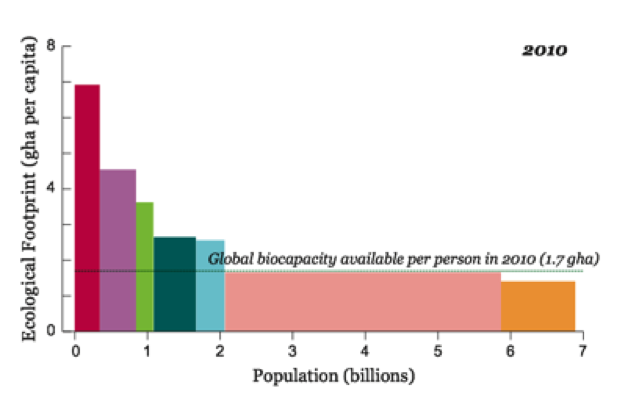

“Reverse development:” sustaining life

Given this reality, the basic premise of international development—that “developing” countries need to develop what the “developed” countries have—seems fatally misguided. One earth would suffice if we all lived as people did in China in 2010. But if everyone on the planet were to live as people do in Canada, we would need 3.7 planets (see figure 2). (WWF, 2014: 59) If poor countries’ economies were to catch up with those of the rich by 2080, the global economy could be more than forty times larger than it is now. (Alexander, 2014: comment) Yet the current economy already far outstrips what Earth can sustain

We can continue the current model of international development, accelerating the monetization of nature until the very basis for our survival is exhausted and our civilization sees a sudden and catastrophic collapse. In this scenario—and that is what we appear to be heading toward if we continue with business as usual—average global living conditions post-collapse might be akin to what they were in the early 20th century. (Turner, 2014: 4) An alternative is to ease away from the edge of the precipice through proactive economic “degrowth.” This means finding ways to meet our needs that require much less throughput of Earth’s material and energy.

Whichever path we take, we will need to turn our understanding of international development around 180 degrees. These times are calling for a radical redefinition of what it is that humanity wants to develop, and who should be helping to develop whom. We might name such a reframing “reverse development.” It is about reversing our understanding of development so that it aims not to convert nature into money, but to sustain and regenerate life. It is also about reversing the flow of learning and support, acknowledging that on a number of levels the “developed” world actually needs what the “developing” world has at least as much as the other way around.

Whichever path we take, we will need to turn our understanding of international development around 180 degrees. These times are calling for a radical redefinition of what it is that humanity wants to develop, and who should be helping to develop whom. We might name such a reframing “reverse development.” It is about reversing our understanding of development so that it aims not to convert nature into money, but to sustain and regenerate life. It is also about reversing the flow of learning and support, acknowledging that on a number of levels the “developed” world actually needs what the “developing” world has at least as much as the other way around.

Less is more

Whether we do it sooner or later, we in the so-called “developed” parts of the world will need to find ways of living well while consuming and throwing away much less. And those in the “developing” parts of the world will need to recover, preserve and cherish what they have already developed, rather than leaving it behind in pursuit of the promise of growth-based development. Together, we all face the deep challenge of finding ways to survive and thrive in an already very depleted world, much in need of restoration.

In modern industrial growth society—indeed in all civilizations since the agricultural revolution—people have “used the creativity of the mind and scientific insight to harness the wonders of technology and increase material wealth.” (Pachamama Alliance, 2010: 11) They have done so with the assumption that they are separate and have dominion over living systems—their bodies, other people, other beings, and the planet itself. Much has been gained, but what has been lost is a basic connection to life, and the ability to sustain it. The more “developed” we are—the more embedded within the globalized, urban, techno-industrial growth society—by definition the less connected to life we tend to be. We know how to manipulate matter on a molecular level and how to modify the very structures of life. But we’ve forgotten how to listen and respect natural rhythms, how to band together at a local community level and meet our own and each other’s needs, how to freely inhabit and enjoy our bodies, how to artistically express the life force that animates us, and most critically, how to live in harmony with creation.

Modern civilization has led us to a precarious brink of time. Recognizing this, a number of emerging social movements are inviting those of us in industrialized parts of the world to live better while using less of the Earth’s material and energy. The Transition movement builds self-reliance at a community level, pro-actively moving away from fossil fuels and re-localizing currencies and food and energy production. The Sufficiency movement stands for the belief that “we are already enough, and already have enough, to create a new world that works for everyone.” (Global Sufficiency Network) The “degrowth” movement encourages us to spend less time producing and consuming and more time enjoying friends, family, culture, creativity and community. And the Slow Movement invites us to slow down and do things as well as possible, instead of as fast as possible.

Those in “less developed” parts of the world are, by definition, less integrated with the globalized techno-industrial economy. They are less dependent on goods and services from around the world to meet their basic needs, and more localized and self-reliant. They use less of the Earth’s fuel and matter to live. They tend to have more time for family, community and creative expression. They move at a slower pace. Because their dependence on the Earth is less mediated by technology, industry, and work done by people in far-off lands, they tend to be more connected to nature. In other words, they have many of the attributes that the social movements mentioned above aim to cultivate among those of us in the “developed” world.

In modern industrial growth society—indeed in all civilizations since the agricultural revolution—people have “used the creativity of the mind and scientific insight to harness the wonders of technology and increase material wealth.” (Pachamama Alliance, 2010: 11) They have done so with the assumption that they are separate and have dominion over living systems—their bodies, other people, other beings, and the planet itself. Much has been gained, but what has been lost is a basic connection to life, and the ability to sustain it. The more “developed” we are—the more embedded within the globalized, urban, techno-industrial growth society—by definition the less connected to life we tend to be. We know how to manipulate matter on a molecular level and how to modify the very structures of life. But we’ve forgotten how to listen and respect natural rhythms, how to band together at a local community level and meet our own and each other’s needs, how to freely inhabit and enjoy our bodies, how to artistically express the life force that animates us, and most critically, how to live in harmony with creation.

Modern civilization has led us to a precarious brink of time. Recognizing this, a number of emerging social movements are inviting those of us in industrialized parts of the world to live better while using less of the Earth’s material and energy. The Transition movement builds self-reliance at a community level, pro-actively moving away from fossil fuels and re-localizing currencies and food and energy production. The Sufficiency movement stands for the belief that “we are already enough, and already have enough, to create a new world that works for everyone.” (Global Sufficiency Network) The “degrowth” movement encourages us to spend less time producing and consuming and more time enjoying friends, family, culture, creativity and community. And the Slow Movement invites us to slow down and do things as well as possible, instead of as fast as possible.

Those in “less developed” parts of the world are, by definition, less integrated with the globalized techno-industrial economy. They are less dependent on goods and services from around the world to meet their basic needs, and more localized and self-reliant. They use less of the Earth’s fuel and matter to live. They tend to have more time for family, community and creative expression. They move at a slower pace. Because their dependence on the Earth is less mediated by technology, industry, and work done by people in far-off lands, they tend to be more connected to nature. In other words, they have many of the attributes that the social movements mentioned above aim to cultivate among those of us in the “developed” world.

The eighth fire

The Anishinaabe Seven Fires Prophecy is one of a number of indigenous prophecies related to this time. It says that their people would be visited by a light-skinned race, and that if these people did not come in friendship, great calamities would befall them. When the water was unfit to drink and the fish unfit to eat, they would know the time had come for a great purification. At that point, the creator would give the light-skinned people a chance to make up for the damage that had been done. In this time of the seventh fire, amidst great confusion and pain, the red and the white people would meet again at a fork in the road. They would have the chance to come together to form a mighty nation, together with the black and yellow peoples, and to walk the red road of earth knowledge and heal the earth. The eighth fire that would follow would be either a fire of light to blow away the darkness and the pains, or a fire to consume and destroy. The choice is ours. (Dostou, in Nalls, 2013)

The red peoples, and indigenous tribal people around the world, have skills and knowledge that the whole world needs in this unprecedented planet-time. Their territories also hold around 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity. (Perkasa and Evanty, 2014) To quote the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, “indigenous, local, and traditional knowledge systems and practices, including indigenous peoples’ holistic view of community and environment, are a major resource for adapting to climate change.” (2014, 26) I’m struck by the case of Bolivia, a country to which I have been travelling since 1998 in the context of my work. One of the “poorest” countries in the hemisphere, Bolivia has the highest proportion of indigenous people in the world (over 60%). After centuries of undeclared apartheid, Bolivia elected its first indigenous president in 2006. It is perhaps no coincidence then that in recent years Bolivia has been a global leader and pioneer in reframing humanity’s relationship with the rest of the Earth community.

In 2009, Bolivia proposed a Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth to the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). In 2010 Bolivia hosted the World Peoples’ Conference on Climate Change and on that occasion adopted the Declaration. That remarkable document, based in the Andean indigenous worldview, recognizes Pachamama (the Quechua word for Mother Earth) as a living being. It declares, among other things, her rights to a clean life and to regenerate her biocapacity, and human beings’ obligations to live in harmony with her. Bolivia’s thought leadership has led to a remarkable array of UNGA initiatives promoting “Harmony with Nature.” These include five UN resolutions, five reports of the UN Secretary General, a dedicated UN website, a study, four interactive dialogues, and the designation of April 22 as International Mother Earth Day.

Domestically, Bolivia, like Ecuador, is creating a global precedent for a new Earth system governance paradigm based in indigenous understandings of humanity’s radical interdependence with nature. It has adopted the indigenous principle and practices of vivir bien (living well) as a foundation for its constitution, legal framework and national planning. The worldview encapsulated in vivir bien—a concept still very much under construction—offers a guide for living in these times. It refers to living in harmony with all other humans and all other beings, including future generations. It includes the notions of relatedness, complementarity, reciprocity, wholeness and equilibrium. These bring vital counterpoints to the underpinnings of modern civilization: separation, domination, competition, specialization, and growth. It sees humans not as separate from nature, but as one component of the larger Earth community, in which everything is life.

The red peoples, and indigenous tribal people around the world, have skills and knowledge that the whole world needs in this unprecedented planet-time. Their territories also hold around 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity. (Perkasa and Evanty, 2014) To quote the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, “indigenous, local, and traditional knowledge systems and practices, including indigenous peoples’ holistic view of community and environment, are a major resource for adapting to climate change.” (2014, 26) I’m struck by the case of Bolivia, a country to which I have been travelling since 1998 in the context of my work. One of the “poorest” countries in the hemisphere, Bolivia has the highest proportion of indigenous people in the world (over 60%). After centuries of undeclared apartheid, Bolivia elected its first indigenous president in 2006. It is perhaps no coincidence then that in recent years Bolivia has been a global leader and pioneer in reframing humanity’s relationship with the rest of the Earth community.

In 2009, Bolivia proposed a Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth to the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). In 2010 Bolivia hosted the World Peoples’ Conference on Climate Change and on that occasion adopted the Declaration. That remarkable document, based in the Andean indigenous worldview, recognizes Pachamama (the Quechua word for Mother Earth) as a living being. It declares, among other things, her rights to a clean life and to regenerate her biocapacity, and human beings’ obligations to live in harmony with her. Bolivia’s thought leadership has led to a remarkable array of UNGA initiatives promoting “Harmony with Nature.” These include five UN resolutions, five reports of the UN Secretary General, a dedicated UN website, a study, four interactive dialogues, and the designation of April 22 as International Mother Earth Day.

Domestically, Bolivia, like Ecuador, is creating a global precedent for a new Earth system governance paradigm based in indigenous understandings of humanity’s radical interdependence with nature. It has adopted the indigenous principle and practices of vivir bien (living well) as a foundation for its constitution, legal framework and national planning. The worldview encapsulated in vivir bien—a concept still very much under construction—offers a guide for living in these times. It refers to living in harmony with all other humans and all other beings, including future generations. It includes the notions of relatedness, complementarity, reciprocity, wholeness and equilibrium. These bring vital counterpoints to the underpinnings of modern civilization: separation, domination, competition, specialization, and growth. It sees humans not as separate from nature, but as one component of the larger Earth community, in which everything is life.

One Earth Community

In practice, Bolivia has not in fact broken away from an extractivist, growth-based economic model. But by bringing Andean understandings of Pachamama and vivir bien into the official discourse of domestic and international governance, it is one of many examples of indigenous peoples recovering and lifting their principles, and practices up onto the world stage. These acts of decolonization liberate not only the colonized but also the colonizers. They offer values and possibilities that all of humanity needs at this time—whether “developed” or “developing,” “modern” or “primitive.” They point toward a path of respect, wisdom and harmony that could just save us—if we choose, together, to form the mighty nation foretold by the Anishinaabe.

These indigenous perspectives, rooted in an understanding of the profound interconnectedness of all things, are pointing the modern world to our own emerging scientific discoveries. The structures and processes of our civilization are based in outdated Newtonian and Cartesian views that are dualistic, anthropocentric and mechanistic. But in the last century, sciences from quantum physics to living systems to cosmology have been revealing a world that is whole, alive and deeply inter-related from the quantum to the cosmic. They are showing us that everything is connected in ways that are hard for us to perceive and fully fathom through the intellect. It is time that our ways of living returned to—and caught up with—deeper understandings of how life works. It is time we restored our connection to life, in service of its continuation on this planet.

This moment asks us to move beyond last century’s contest between capitalist and communist models of development. Seen from a life-oriented perspective, those two ideologies are more similar than different. They both assume separation between the human and more-than-human world and promote monetization and commoditization of one by the other. Both end up destroying the very foundations necessary for life on Earth. What is needed is nothing less than an evolutionary leap into the unknown—unprecedented approaches to match unprecedented conditions. This is a time to feel our way forward into patterns of being that allow life to flourish. For this, we need to root ourselves in both ancient knowing and emerging knowledge.

Ultimately, “reverse development” is about humility and courage in the face of an uncertain future. It is about calling upon the widest, wildest and wisest humanity in people in both the “developing” and “developed” parts of the planet. Everyone brings a vital element; nobody has the solutions. Because the “developed” have spent so long teaching the “developing” how to emulate their ways, there is a time and place for reversing that flow and focusing on what can be learned from traditional, local and indigenous peoples. They have ways of entering into active relationship and two-way communication with the beings of all species and of all times—ways that life wants us all to value and grow. But in the long run, people from all parts of the world are being called to come together in a spirit of not-knowing. We have just one Earth to sustain all members of the community of life. As humans, our task now is to learn how to thrive as an inseparable part of a single Earth community. To do so, as individuals and as peoples we must draw upon the deepest groundwaters, each from our own well.

“Reverse development” is also about humility in the face of another. It is about dropping our notions of teacher and taught, “developer” and “developing,” and coming together as partners. We gather across culture and place as friends, to work and learn together. An example of this is the translocal model of the Berkana Exchange, in which communities in “developed” and “developing” countries alike find what they need “in themselves—in everyday people, their cultural traditions and their environment.” They use “this wisdom and wealth to conduct bold experiments in how to create healthy and resilient communities where all people matter, all people can contribute.” And, coming from places around the globe, they support each other through the process, weaving through each other’s lives, visiting one another’s communities, and gathering together to share their discoveries and dilemmas. (Wheatley and Frieze, 2011: 5)

These indigenous perspectives, rooted in an understanding of the profound interconnectedness of all things, are pointing the modern world to our own emerging scientific discoveries. The structures and processes of our civilization are based in outdated Newtonian and Cartesian views that are dualistic, anthropocentric and mechanistic. But in the last century, sciences from quantum physics to living systems to cosmology have been revealing a world that is whole, alive and deeply inter-related from the quantum to the cosmic. They are showing us that everything is connected in ways that are hard for us to perceive and fully fathom through the intellect. It is time that our ways of living returned to—and caught up with—deeper understandings of how life works. It is time we restored our connection to life, in service of its continuation on this planet.

This moment asks us to move beyond last century’s contest between capitalist and communist models of development. Seen from a life-oriented perspective, those two ideologies are more similar than different. They both assume separation between the human and more-than-human world and promote monetization and commoditization of one by the other. Both end up destroying the very foundations necessary for life on Earth. What is needed is nothing less than an evolutionary leap into the unknown—unprecedented approaches to match unprecedented conditions. This is a time to feel our way forward into patterns of being that allow life to flourish. For this, we need to root ourselves in both ancient knowing and emerging knowledge.

Ultimately, “reverse development” is about humility and courage in the face of an uncertain future. It is about calling upon the widest, wildest and wisest humanity in people in both the “developing” and “developed” parts of the planet. Everyone brings a vital element; nobody has the solutions. Because the “developed” have spent so long teaching the “developing” how to emulate their ways, there is a time and place for reversing that flow and focusing on what can be learned from traditional, local and indigenous peoples. They have ways of entering into active relationship and two-way communication with the beings of all species and of all times—ways that life wants us all to value and grow. But in the long run, people from all parts of the world are being called to come together in a spirit of not-knowing. We have just one Earth to sustain all members of the community of life. As humans, our task now is to learn how to thrive as an inseparable part of a single Earth community. To do so, as individuals and as peoples we must draw upon the deepest groundwaters, each from our own well.

“Reverse development” is also about humility in the face of another. It is about dropping our notions of teacher and taught, “developer” and “developing,” and coming together as partners. We gather across culture and place as friends, to work and learn together. An example of this is the translocal model of the Berkana Exchange, in which communities in “developed” and “developing” countries alike find what they need “in themselves—in everyday people, their cultural traditions and their environment.” They use “this wisdom and wealth to conduct bold experiments in how to create healthy and resilient communities where all people matter, all people can contribute.” And, coming from places around the globe, they support each other through the process, weaving through each other’s lives, visiting one another’s communities, and gathering together to share their discoveries and dilemmas. (Wheatley and Frieze, 2011: 5)

And this brings me back to the TLC. In each of the gatherings I’ve attended, the TLC has done a remarkable job of lifting up the knowledge and wisdom of those whom the mainstream development paradigm would assume to be in need of development and learning. Instead, the TLC invites in people from the “developing” world and from indigenous cultures on all continents, not as “beneficiaries” or even merely as participants, but as respected wisdom leaders. At each TLC event, I have seen such leaders take their rightful and proportionate place as conference speakers and as stewards of TLC-associated research projects around the world.

The TLC does more than just pay lip service to the notion of “honouring diversities of knowledge from all four directions.” It recognizes the initiatory leadership of indigenous people in honouring “the more-than-human world as all our relations,” and tends the indigenous spark waiting to be rekindled in the rest of us. (TLC) It gathers us in from all directions as friends, partners, and colleagues to learn alongside one another. It creates a sacred playground in which we can share our hearts, listen together for what wants to be known, and feel our way forward into the unprecedented future that beckons. This is what “reverse development” looks like. We ignite each others’ life-light until the whole Indra’s net is gleaming—the new One Earth society that is waiting to be born.

The TLC does more than just pay lip service to the notion of “honouring diversities of knowledge from all four directions.” It recognizes the initiatory leadership of indigenous people in honouring “the more-than-human world as all our relations,” and tends the indigenous spark waiting to be rekindled in the rest of us. (TLC) It gathers us in from all directions as friends, partners, and colleagues to learn alongside one another. It creates a sacred playground in which we can share our hearts, listen together for what wants to be known, and feel our way forward into the unprecedented future that beckons. This is what “reverse development” looks like. We ignite each others’ life-light until the whole Indra’s net is gleaming—the new One Earth society that is waiting to be born.

References

Alexander, Samuel (October 1 2014). “Life in a ‘degrowth’ economy, and why you might actually enjoy it.” “The Conversation” website. Retrieved December 19, 2014 from http://theconversation.com/life-in-a-degrowth-economy-and-why-you-might-actually-enjoy-it-32224

Carpenter, Duane. “Part 6: Indra’s Net and the Worldwide Web.” Dynamic Symbols II: The Vortex and the Path to Liberation. Retrieved December 30, 2014 from http://www.light-weaver.com/vortex/6indra.html

Global Footprint Network (2014). “Footprint Basics—Overview,” in Global Footprint Network website. Retrieved December 19, 2014 from http://www.footprintnetwork.org/en/index.php/GFN/page/footprint_basics_overview/

Global Sufficiency Network (n.d.). “Global Sufficiency Network—About Us.” Retrieved December 26, 2014 from http://www.sevenstonesleadership.com/global-sufficiency-network-about-us/

Griffiths, Jesse (2014). The State of Finance for Developing Countries, 2014: An assessment of the scale of all sources of finance available to developing countries. Brussels: European Network on Debt and Development. Retrieved December 18 2014 from http://www.eurodad.org/files/pdf/5492f601aeb65.pdf

Hall, Gillette H and Patrinos, Harry Anthony, Eds. (2012). Indigenous Peoples, Poverty, and Development. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2014). Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability: Summary for Policymakers. Retrieved on December 27, 2014 from https://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/wg3/WGIIIAR5_SPM_TS_Volume.pdf

Meadows, Donella H, Meadows, Dennis L. and Randers, Jorgen (1992). Beyond the Limits: Confronting Global Collapse, Envisioning a Sustainable Future. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing Company.

Nalls, Gayil (Creator and Poster) (2013). Tom Dostou: The Seven Fires Prophecy [Video] Retrieved on December 31 2014 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=STVfqA0KUM0

The Pachamama Alliance (2010). Awakening the Dreamer, Changing the Dream Symposium V-2 Presenter’s Manual. San Francisco: The Pachamama Alliance.

Perkasa, Vidhyandika and Evanty, Nukila (2014). “The World Conference on Indigenous Peoples: A View From Indonesia.” Retrieved December 27, 2014 from http://www.cfr.org/councilofcouncils/global_memos/p33476

Perkins, John (2004). Excerpt from prologue, Confessions of an Economic Hit Man. Berrett-Koehler Publishers. Retrieved December 18, 2014 from https://www.bkconnection.com/books/title/the-new-confessions-of-an-economic-hit-man

Quinn, Daniel (1992). Ishmael. New York: Bantam/Turner Books.

Quinn, Daniel (1996). The Story of B. New York: Bantam Dell.

Quinn, Daniel (1997). My Ishmael. New York: Bantam Books.

Transformative Learning Center—TLC (2013). “Background” page of TLC Momentum Gathering website. Retrieved on December 28 2014 from http://www.momentumtlc.com/backgroud/

Turner, Graham (2014). “Is Global Collapse Imminent? An Updated comparison of The Limits to Growth with Historical Data,” MSSI Research Paper No. 4, Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute, The University of Melbourne.

United Nations (2011). World Economic Situation and Prospects 2011, 69 Retrieved December 18 2014 from http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/wesp/wesp_archive/2011chap3.pdf

Wheatley, Margaret and Frieze, Deborah (2011). Walk Out Walk On: A Learning Journey into Communities Daring to Live the Future Now. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

World Wildlife Fund (2014). Living Planet Report 2014: Species and Spaces, People and Places. Gland, Switzerland: World Wildlife Fund International. Retrieved December 19, 2014 from http://awsassets.wwf.ca/downloads/lpr2014_low_res__1_.pdf

Wright, Ronald (2004). A Short History of Progress (CBC Massey Lectures Series). Toronto: House of Anansi Press.

Carpenter, Duane. “Part 6: Indra’s Net and the Worldwide Web.” Dynamic Symbols II: The Vortex and the Path to Liberation. Retrieved December 30, 2014 from http://www.light-weaver.com/vortex/6indra.html

Global Footprint Network (2014). “Footprint Basics—Overview,” in Global Footprint Network website. Retrieved December 19, 2014 from http://www.footprintnetwork.org/en/index.php/GFN/page/footprint_basics_overview/

Global Sufficiency Network (n.d.). “Global Sufficiency Network—About Us.” Retrieved December 26, 2014 from http://www.sevenstonesleadership.com/global-sufficiency-network-about-us/

Griffiths, Jesse (2014). The State of Finance for Developing Countries, 2014: An assessment of the scale of all sources of finance available to developing countries. Brussels: European Network on Debt and Development. Retrieved December 18 2014 from http://www.eurodad.org/files/pdf/5492f601aeb65.pdf

Hall, Gillette H and Patrinos, Harry Anthony, Eds. (2012). Indigenous Peoples, Poverty, and Development. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2014). Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability: Summary for Policymakers. Retrieved on December 27, 2014 from https://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/wg3/WGIIIAR5_SPM_TS_Volume.pdf

Meadows, Donella H, Meadows, Dennis L. and Randers, Jorgen (1992). Beyond the Limits: Confronting Global Collapse, Envisioning a Sustainable Future. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing Company.

Nalls, Gayil (Creator and Poster) (2013). Tom Dostou: The Seven Fires Prophecy [Video] Retrieved on December 31 2014 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=STVfqA0KUM0

The Pachamama Alliance (2010). Awakening the Dreamer, Changing the Dream Symposium V-2 Presenter’s Manual. San Francisco: The Pachamama Alliance.

Perkasa, Vidhyandika and Evanty, Nukila (2014). “The World Conference on Indigenous Peoples: A View From Indonesia.” Retrieved December 27, 2014 from http://www.cfr.org/councilofcouncils/global_memos/p33476

Perkins, John (2004). Excerpt from prologue, Confessions of an Economic Hit Man. Berrett-Koehler Publishers. Retrieved December 18, 2014 from https://www.bkconnection.com/books/title/the-new-confessions-of-an-economic-hit-man

Quinn, Daniel (1992). Ishmael. New York: Bantam/Turner Books.

Quinn, Daniel (1996). The Story of B. New York: Bantam Dell.

Quinn, Daniel (1997). My Ishmael. New York: Bantam Books.

Transformative Learning Center—TLC (2013). “Background” page of TLC Momentum Gathering website. Retrieved on December 28 2014 from http://www.momentumtlc.com/backgroud/

Turner, Graham (2014). “Is Global Collapse Imminent? An Updated comparison of The Limits to Growth with Historical Data,” MSSI Research Paper No. 4, Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute, The University of Melbourne.

United Nations (2011). World Economic Situation and Prospects 2011, 69 Retrieved December 18 2014 from http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/wesp/wesp_archive/2011chap3.pdf

Wheatley, Margaret and Frieze, Deborah (2011). Walk Out Walk On: A Learning Journey into Communities Daring to Live the Future Now. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

World Wildlife Fund (2014). Living Planet Report 2014: Species and Spaces, People and Places. Gland, Switzerland: World Wildlife Fund International. Retrieved December 19, 2014 from http://awsassets.wwf.ca/downloads/lpr2014_low_res__1_.pdf

Wright, Ronald (2004). A Short History of Progress (CBC Massey Lectures Series). Toronto: House of Anansi Press.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed